“I’ve never heard an intelligent discussion about ‘cost of capital’.” – Charlie Munger

I read something a few weeks back that referenced some comments that Charlie Munger once made on the topic of cost of capital. Maybe these comments will be yet another unintelligent discussion of cost of capital, but I thought I’d share some notes I wrote down this past week as I gave this concept some more thought. This post will touch on Buffett’s $1 test, which is how he thought about a company’s cost of capital, and then in the next post I’ll outline the cost of capital concept and how I like to think about it when thinking about investment ideas.

The cost of capital is a very simple concept, but it’s also one that for some reason becomes very confusing, theoretical, and abstract (especially if you consult most textbooks on corporate finance). The phrase “cost of capital” is often used in conjunction with “return on capital”, and both can be mired in either academic theory or the false sense of precision that comes from manipulating numbers in a spreadsheet.

As usual, Buffett has some common sense things to say about the relationship between returns on capital and cost of capital, and sums it up best with what he has called the $1 test.

From Buffett’s 1984 shareholder letter:

“Unrestricted earnings should be retained only when there is a reasonable prospect – backed preferably by historical evidence or, when appropriate, by a thoughtful analysis of the future – that for every dollar retained by the corporation, at least one dollar of market value will be created for owners. This will happen only if the capital retained produces incremental earnings equal to, or above, those generally available to investors.”

So what is Buffett saying here?

Three things:

- Value creation comes from the returns that the company can generate on reinvested cash (incremental returns on capital), not just the returns they generate on previously invested capital (ROIC)

- Companies should only retain earnings if a dollar in the company’s hands is more valuable than a dollar in the shareholder’s hands.

- The only way a company achieves #2 is to earn a higher return on that dollar than shareholders could earn elsewhere (which is another way of saying companies must produce returns on capital that exceed their cost of capital)

When Buffett talks about a dollar of retained capital creating a dollar of market value, he’s talking about the stock price over time (he said later in that 1984 letter that he’d evaluate this over a five year period). He’s talking about a dollar of intrinsic value, but he’s implying that the stock market will be a fairly accurate judge of intrinsic value over time. And he’s saying that the market over time will reward businesses that create high returns on the dollars they keep (by giving them a higher market value, i.e. stock price), and the market will punish (with a lower valuation) those companies whose dollars retained fail to earn their keep.

Simple Example $1 Test

To look at a very simplified example, let’s assume an average stock market valuation of 10 P/E, or in other words, a 10% earnings yield (which was roughly what stocks were valued at on average when Buffett wrote these words in the early 1980’s). If a company valued by the market at $100 million earns a profit of $10 million and retains all of those earnings, the company will only increase the value by $10 million if it can earn an incremental return on that $10 million that exceeds what shareholders could earn elsewhere. In this example, shareholders have plenty of other alternatives to earn a 10% return on their capital (since the market average in this case has a 10% yield). So if the company can earn a 10% return on that retained $10 million, then its earnings will rise to $11 million the following year, and assuming the same valuation of 10 P/E, the business would now be valued at $110 million, thus passing Buffett’s $1 test. The $10 million of retained earnings created additional market value of $10 million.

This isn’t a great return, as Buffett would be looking for retained earnings to create more value than just matching the cost of capital, but this is the minimum requirement that the company must meet in his mind (note that if earnings were distributed, an individual would actually have to earn a higher return on those incremental earnings than what the company earns internally to account for capital gains taxes on the dividend, but this simple example illustrates what Buffett is trying to get across).

It’s worth noting that Buffett doesn’t use the phrase “cost of capital”, and he doesn’t think about the concept the way most people in finance think about it. Munger said they’ve never used that phrase in practice.

However, just like DCF’s (which is a tool Buffett is skeptical of in practice, despite agreeing with the general method in principle), Buffett and Munger essentially do the cost of capital calculation in their head. They implicitly use and understand both DCF’s and cost of capital calculations even if they don’t explicitly label them.

Return on Incremental Invested Capital

Value is created when companies earn returns on capital that exceed their cost of capital. In the next post, I’ll outline my own thoughts on how to think about cost of capital, and what that really means, but despite Buffett and Munger’s dislike for the term, they clearly understand and utilize the concept when they make investment decisions. But for now, I’ll review the other piece that Buffett is talking about, which is that the growth of a company’s intrinsic value depends on the returns it can earn on its incremental capital investments.

When I analyze companies, I always try to figure out what I think their returns on incremental capital will be going forward, as that is a key variable in determining the rate at which the company’s intrinsic value will compound at over time. I’ve written about the importance of ROIC in the past, in a series of posts (read them here), but basically, a firm’s value will grow at the product of its returns on incremental capital times the amount of earnings it can reinvest (plus any added benefit to allocating the portion of capital that couldn’t be reinvested back into the business).

Saber Capital’s Basic Investment Objective

My investment firm’s strategy is centered around the idea that companies can be put in one of two main buckets:

- Those companies that will be more valuable in five years or so, and

- Those that will be worth less.

As the former Michigan football coach Bo Schembechler once said, each day you’re either getting better or you’re getting worse, but you’re not staying the same.

So given this simple idea about two main buckets of companies, I try to stay focused on the first bucket – those companies that will have a higher intrinsic value (the present value of the future cash flows will either be higher or lower in five years). As we know, stock prices can fluctuate wildly in the short-run, but over time they will converge with their intrinsic value. And if that value is marching upward over time, it becomes a tailwind for me rather than a headwind. Another way of saying this is that my margin of safety (any gap between my purchase price and intrinsic value) widens over time.

One way of filtering the universe to find “1st Bucket” companies is to figure out if the company is passing Buffett’s $1 test.

Google’s $1 Test

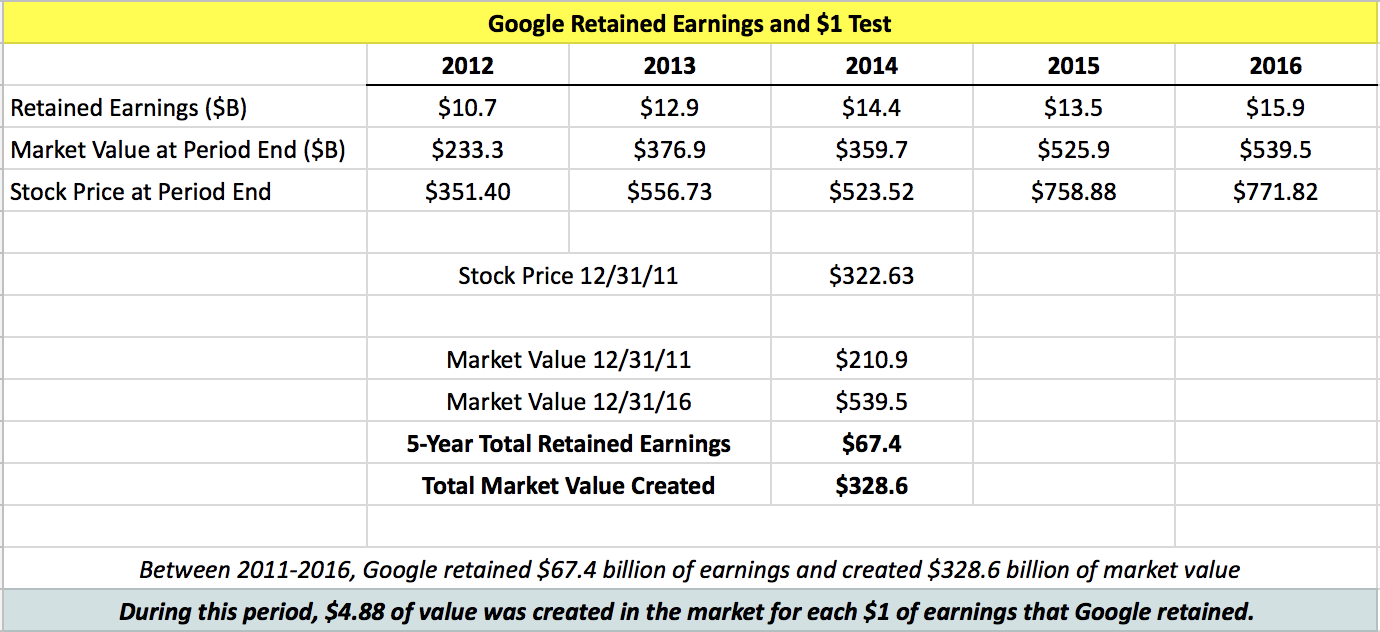

Alphabet (Google) is a obviously a great business, and so I glanced at the last five years of numbers to see how it fared in Buffett’s $1 test. Buffett said in that 1984 letter that because the market is obviously volatile, he preferred looking at a longer period of three to five years to be able to draw conclusions on whether that dollar of retained earnings actually created real value.

So here is a look at the overall value GOOG created from each $1 of retained earnings:

This is just a quick way to glance at the returns that Google is generating from its incremental capital. It doesn’t measure the returns on capital specifically and obviously leaves plenty to be analyzed, but it does show that Google has been very productive with the earnings it has kept (creating nearly $5 of market value for shareholders for each $1 it retained during this 5-year stretch).

Note that this doesn’t include 2017, which has seen tech stocks soar to new heights (Google is up over 30% YTD). Some have quibbled with Google’s approach to “other bets” (financed through the huge cash flow of its incredibly profitable core search business – Google spent over $1 of every $4 of revenue on R&D and capex last year and still made around $20 billion of free cash flow!).

We’ll see how/if/when the other bets pay off, but I think it’s reasonable to conclude that Google is creating plenty of value for shareholders by retaining earnings.

Incremental ROIC and Buffett’s $1 Test

The way Buffett measures whether a firm can create $1 of market value for each $1 of retained earnings is to measure whether the returns on those earnings exceed what shareholders can earn elsewhere (at a given level of risk). So what Buffett is talking about here is the return on incremental capital, or ROIIC, which is really the entire point of trying to analyze a firm’s ROIC.

I outline a back of the envelope way to estimate a firm’s ROIIC in this post, but basically, the point behind this concept is that we want to know what returns the company will generate on its investments going forward. We can look at the return on capital it previously invested (which is what ROIC measures) as a proxy or guide for what the company might earn going forward, but what matters to us as investors is what the company will do with its capital from this point forward. It really doesn’t matter that a firm has a 50% ROIC if there is nowhere to invest earnings at that rate going forward. That still might be a good business that throws off a lot of cash flow, but what we really want to know as potential owners is what the future returns on incremental investments will be, as that is what will determine how quickly the earning power of the business (and thus the intrinsic value) will compound.

In the simple example above of the company that retains and reinvests $10 million of earnings and has $100 million market value (P/E of 10), if the company only earned a 5% return on that retained capital, then that $10 million would only produce $500,000 of earnings growth, or 5%, which is unlikely to be better than alternative options for owners. You could take your piece of that $10 million and invest it elsewhere at a rate higher than 5%. Over time, the market would likely begin to devalue these retained earnings such that each incremental dollar the company reinvested (that only produces 5% in a world where 10% is attainable) would wind up getting valued at less than a dollar in the stock market.

On the other hand, if the company earned 20% returns on that retained capital, then earnings would grow by $2 million for a total of $12 million of earnings, and the value of the business would be $120 million at the same P/E of 10, meaning that $10 million of retained earnings created $20 million of additional market value. $2 of market value was created for each $1 retained in this case.

Now, P/E ratios obviously don’t remain static. In reality, the business that earned just 5% in a world of 10% earnings yields would likely see the valuation decline, thus not only failing to produce adequate ROIC, but the market would also value the earnings at a lower multiple, thus clearly failing Buffett’s $1 test.

And the business that generates a 20% ROIC will likely see its $12 million earnings garner a higher P/E. At 12 P/E, the business is now worth $144 million, thus creating $4.40 of value for each $1 it retained, and thus clearly passing Buffett’s $1 test.

To Sum It Up

So like so many other lessons, Buffett uses a common sense approach to thinking about returns on capital and cost of capital. With the $1 test, he is clearly talking about cost of capital, and he clearly is judging company returns on capital relative to that cost of capital, but he is doing it in a much more common sense way that has more practical use than trying to figure out industry betas, equity risk premiums, WACC, etc…

The next post will have some more notes on how I like to think about cost of capital including the differences between what companies estimate their cost of capital to be going forward and what it actually turns out to be (the difference largely due to the inefficiencies of the stock market). I’ll also mention why measuring your opportunity costs is the most logical way to think about cost of capital, and I’ll have an example of how Buffett thinks about cost of capital using one of his investment mistakes.

Have a great week!

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, dressme.co.nz/ball-dresses.html”>LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

To read more of John’s writings or to get on Saber Capital’s email distribution list, please visit the Letters and Commentary page on Saber’s website. John can be reached at [email protected].