“The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power. If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

–Warren Buffett, 2011 (Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission)

I wrote a post about Amazon a couple weeks ago. I think Amazon is a great business, and regardless of the price of the stock, I think it’s a business worth studying.

One aspect of Amazon’s model that is worth thinking about is their potential real pricing power. My friend and fellow investor Josh Tarasoff of Greenlea Lane has some interesting things to say regarding pricing power, and he thinks about this subject differently than most investors.

Basically, as value investors, we are all conditioned to think linearly when it comes to pricing power. How often have we heard Buffett talk about See’s Candies and how every December 26th they raise prices? This is a very attractive business to own. In other words, a business that can raise prices each year in a nice, steady upward trend is ideal. This is a business that we say has pricing power, as it can increase the cost of its product or service to reflect the general increase in prices (inflation).

But Tarasoff brings up three really good points regarding pricing power:

- Nominal vs Real Pricing Power: A business that can increase prices at a rate that only offsets inflation is good, but not exceptional (if it can’t raise nominal prices at a level that meets the inflation rate, it’s a bad situation). Ideally what we’d like is a business that can raise prices in excess of inflation (real pricing power).

- Real pricing power actually indicates an inefficiently priced product or service. In other words, just as stock prices occasionally get priced below fair value, sometimes a business’s products or services get priced below fair value to a customer. This undervalued product is a source of potential value as a business begins to price their product more efficiently (raise prices in real terms).

- Real pricing power is finite. Just like a stock that reaches fair value and is no longer mispriced, at some point, a businesses’ ability to increase real prices without impacting unit volume comes to an end. This means that a long history of real price increases doesn’t necessarily indicate future real price increases.

Let’s discuss the first point…

Nominal vs. Real Pricing Power

If you are a business owner, the minimum amount of pricing power that you would demand is to be able to price your goods or services in a way that keeps up with inflation. If you can’t offset inflation, you don’t have a very good situation. So nominal pricing power is really just a necessary, but not sufficient condition of business quality. A better situation for a business owner would be the ability to raise the prices of his product or service in excess of inflation. This type of real pricing power can create significant value for owners.

This is rare. It is also inefficient. And it leads us to the second bullet point…

Real Pricing Power = Undervalued (Mispriced) Products

If a business can raise prices in excess of inflation, it actually means that it is not actually maximizing its current pricing. In other words, if a business can actually raise prices in excess of inflation without negatively impacting unit volume, it was not charging as much as it could have prior to the real price increase.

Tarasoff likens this “inefficiency” to a stock that is “inefficiently priced” in the market. Just like there are undervalued stocks, there are also undervalued products and services. This means that customers are getting a bargain. They collectively would be willing to pay more in real terms for the same product or service. In this situation, businesses can raise their prices in real terms without affecting unit volume, creating an enormous amount of value for their shareholders.

All Good Things Must End—Point 3

Now, although some companies can experience very long periods of real price increases, it is true that real pricing power is finite. There is only a certain amount of real pricing power that a business has before it reaches the maximum price per unit that it can operate at without negatively impacting volume.

The contrarian aspect of Tarasoff’s thinking is that while it’s nice to see a business that has consistently raised its prices, it might actually be better to find a business that has not raised its prices in a long time for one reason or another, thus causing its product or service to become underpriced—and undervalued to customers. This situation creates a sort of pent-up pricing power that can be released in the form of future real price increases for a certain amount of time.

Look For Undervalued Products/Services

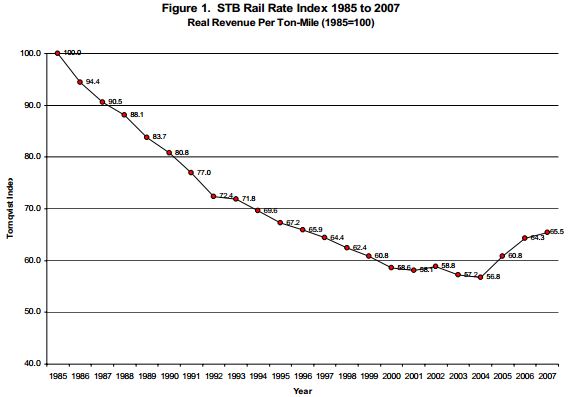

Tarasoff references the railroad industry as a general example of this type of thinking… real prices declined for decades until 2004, creating an underpriced service and pent-up pricing power for a consolidated industry.

Some were surprised when Buffett made a massive acquisition of a major railroad in 2009, as these capital intensive businesses are typically not what Buffett finds attractive. But as the quote at the top of this post suggests, Buffett has pricing power at the top of his investment wish list, and Burlington Northern Santa Fe certainly has the potential to grant this wish.

There are other examples of general situations that can lead to potential real pricing power—one is the situation that occurs when a not-for-profit organization converts into a for-profit business. This change in structure can lead to more efficient prices, as management and owners are incentivized differently in for-profit enterprises.

And occasionally it is not an industry trend or a structural change, but simply an individual business case where for some reason, management has not priced its products or services correctly, leading to pent-up pricing power. Occasionally a management team discovers that their business possesses the ability to raise real prices—a pleasant finding that they may not have been aware of previously.

To Sum It Up

The main idea here—which I think is quite contrary to what most investors do—is that in order to find real pricing power, it might be helpful to locate businesses that have NOT raised prices for a long period of time for some reason. It’s an interesting take…

I still love finding the See’s type businesses with a history of price increases, but I can understand Tarasoff’s logic that real pricing power can only exist for a finite period of time, and so a business with a history of raising real prices might be nearing the end of its run (as its product becomes more fairly priced), which might cause investors to overvalue this real pricing power, and thus place too much emphasis on the business’ margin expansion and future earning power.

Like a stock that has gone up faster than its value, a long history of real pricing power and margin expansion may mean that the business’ products/services are now much more “fully valued” than they once were.

To summarize these thoughts on real pricing power:

- Pricing power is good

- Real pricing power (as opposed to just nominal pricing power) is what we really want as business owners

- Nominal pricing power (ability to offset inflation) is really the minimum pricing power we would demand as a business owner

- Just like we search for undervalued, or “mispriced” stocks, we should also be on the lookout for undervalued, or “mispriced” products or services (or “untapped pricing power”), as both situations eventually tend to correct themselves creating future value for shareholders.