A while back I wrote a post about how the gap between 52 week high and low prices presents an opportunity for investors in public markets.

I mentioned that this simple observation (the huge gap between yearly highs and lows) is all the evidence you need to debunk the theory that markets are efficiently priced all the time. I think the market generally does a good job at valuing companies within a range of reasonableness, but there is absolutely no way that the intrinsic values of these multibillion dollar organizations fluctuate by 50%, 80%, 120%, 150% or more during the span of just 52 weeks.

The market is constantly serving up opportunities. I just checked a screener and there are 375 stocks in the US that are 50% higher than they were 1 year ago today.

This leads me to a thought that I think, for some reason, is not really discussed in investing circles—at least not in value investing circles: and that is the concept of portfolio “turnover”.

To think about portfolio turnover, let’s first take a look at a concept that security analysts and value investors think about more often: asset turnover.

Asset turnover basically measures how efficient a company is at using the resources it has to generate revenue. It’s simply a company’s revenue in a given period divided by its assets. Generally speaking, asset turnover is a good thing—the higher the better. If two companies have the same asset base, the company with the higher level of sales is doing a better job at employing those assets.

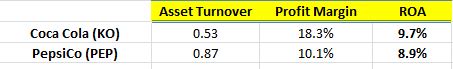

Coke and Pepsi are somewhat similar businesses, but it isn’t necessary to compare their business models when it comes to understanding the math of turnover. Just look at how Coke’s profit margins are almost double the margins at Pepsi, but Pepsi is about equally profitable (produces similar returns on assets) because Pepsi is more efficient than Coke is at using the assets it has.

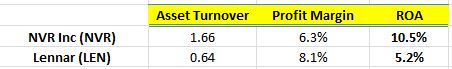

Let’s glance at two homebuilders:

NVR has a different business model than Lennar as it uses less capital (it employs a smaller asset base). This allows NVR to be almost three times more efficient with its resources than Lennar, and although Lennar has a higher profit margin, NVR produced a much better return on assets.

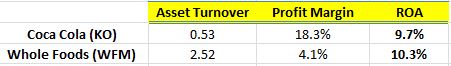

We can compare two businesses in different industries to see how their business models and operating results affect their profitability:

Coke and Whole Foods produce roughly the same ROA, but got there in very different ways… Coke has very high profit margins but takes nearly 2 years to produce $1 of revenue for every $1 of assets. Meanwhile, Whole Foods’ profit margin is less than 1/4th the size of Coke’s, but it turns over its asset base nearly 5 times faster, yielding roughly the same return on the resources it has to deploy.

These examples aren’t to say one business or one measurement is better than the other–it’s really just to point out the importance of turnover.

Inventory turnover is a similar ratio. A grocery store is a very low margin business, but in some cases grocers can produce adequate (or sometimes better than adequate) returns on capital if they are able to turn their inventory (merchandise on the shelves) faster than competitors. Two competitors with identically low profit margins might have vastly different profitability because one grocer might be producing much higher ROA due to its ability to turn its inventory over faster.

So in business, it is clear that asset turnover (and inventory turnover) is a good thing. The higher the turnover, the higher the returns.

Portfolio Turnover

I once mentioned I have put together notes on investors who have achieved exceptional (20-30% annual returns or better) over a long period of time (say 10-15 years minimum). There are a variety of strategies and tactics employed, but there are a few common denominators. In addition to the expected commonalities (most are value investors), there is one common denominator that isn’t talked about much: portfolio turnover.

Basically, think of portfolio turnover as asset turnover.

The capital you have in your account might consists of stocks, bonds, cash, etc… these are your assets. The faster you turn these assets over (at any given level of profit), the better.

It’s simple math. I think a lot of value investors get hung up on the Buffett 3.0 version. Seth Klarman once said that Buffett’s career has evolved a few different times and can be categorized generally as follows:

- Stage 1: Classic Graham and Dodd deep value and arbitrage (special situations)

- Stage 2: Great businesses at really cheap prices (think American Express after Salad Oil Scandal, Washington Post, Disney—the first time at 10 times earnings in the 60’s)

- Stage 3: Great businesses at so-so prices

Now, if we look at Buffett’s results, even lately, some might take issue with Klarman calling them “so-so” prices. But nevertheless, I think Klarman is basically correct in his assessment of Buffett’s career, and I actually think Buffett himself would agree with this. As Buffett’s capital base expanded, he had to begin to begrudgingly adjust the investment hurdle rate that he required. He mentions this in his 1992 letter to shareholders, replacing his demand for “a very attractive price” with simply “an attractive price”.

This description by Klarman took place during an interview with Charlie Rose, and Klarman jokes that he (Klarman) is still in Stage 1, scavenging for bargains. What’s interesting about this comment, is Klarman has been able to produce really solid returns on a very large amount of capital, and I think it’s in large part because of the simple math of asset turnover—Klarman buys bargains, waits for them to be valued at a more reasonable level, sells them, and repeats.

Walter Schloss was another master at turning over his portfolio that was filled with bargains. Schloss actually ran his portfolio like a grocery store. I’d say on balance, his stocks produced relative small profits (I’d venture Schloss had many 20-50% gainers, but very few 5-10 baggers), but collectively, he produced 20% annual returns for nearly 50 years because he was able to adequately turn over his “inventory” (i.e. his stocks) fast enough. This isn’t to say that you have to look for activity, or actively trade—Schloss said he kept his stocks an average of 3-4 years. But it just means that he would not have produced anywhere near the results he did if he held his stocks “forever”, or for 10 years instead of 4, etc…

Walter Schloss was akin to the low margin grocery store that didn’t produce exciting margins on any one product, but collectively across the store it was able to effectively turn over the merchandise fast enough to make exceptional returns on the assets it employed.

Some other investors might be more akin to the higher margin, lower turnover businesses that might produce much lower asset and inventory turns, but still generates very attractive returns on capital because of its very high return on sales (profit margin). These investors hold stocks for longer periods of time, but find big winners that rise 3, 5, 10 times in value over many years. A business can produce incredible profitability on lower asset turnover if it can wring out a large amount of bottom line earning power from its top line revenue.

The Two Drivers of Profitability

Some people might be familiar with the simple math of this situation, but it might help to briefly illustrate this to show what ROA (Return on Assets) consists of:

The Return on Assets (ROA) is one measure of profitability and it is calculated simply by dividing net income into total assets. A lemonade stand that produces $20 of earnings and has $100 worth of assets (the stand, the small square of front lawn, the inventory of lemonade, etc…) is producing a 20% return on assets.

The two functions that determine ROA are:

- Profit Margin (some accountants refer to this as “Return on Sales”). Profit margin is calculated as follows:

- Profit Margin = Net Income/Sales

- Asset Turnover (the measure of how efficiently a business uses its assets—i.e. how much revenue can be generated from each $1 of assets). Asset turnover is calculated as follows:

- Asset Turnover = Sales/Assets

So I hear a lot of people talking about the profit margins (big winners) but few investors talk much about asset turnover (how quickly you go from one investment to the next). And worse yet, when they do discuss turnover, it’s usually negative (most investors say lower turnover is better, which is not true—more on this shortly).

Higher Turnover Isn’t Necessary—But It Does Influence Returns

Now, it’s important to keep in mind the above equation—there are two drivers of profitability of a business:

- Efficiency—how much revenue you can produce from your available resources (assets)

- Profitability—how much profit you earn for each $1 of sales

So, turnover (whether we’re talking about asset turnover in the context of a business, or portfolio turnover in the context of an investment account) is just one driver of the returns that the business (or portfolio) generates.

The other driver is how much money you make on each $1 of sale (or each $1 invested).

If your business begins to turn over its assets more slowly (i.e. it begins to generate less revenue per $1 of assets), then you’ll need to make up for that by earning a higher profit margin on each $1 of revenue if you are to maintain the same ROA.

Similarly, as an investor, if your portfolio turnover decreases (which is often the result of a longer time horizon), your profit margin (in the context of investing, the amount of money you make on each $1 invested) must increase if you are to maintain the same level of annual returns on your overall portfolio.

I think this is where there is somewhat of a disconnect in the value investing community—which often considers portfolio turnover to be a negative thing. In and of itself, turnover is not bad. In fact, generally speaking, the math tells us that it is one of two main drivers of investment performance. So it’s actually necessary!

Why Do Investors Think Portfolio Turnover is Bad?

I think the reason for this negative connotation is that portfolio turnover is often associated with excess, or inappropriately high levels of trading, which is often done for emotional reasons without regard for the fundamentals of the business.

But let’s assume you are a rational, disciplined value investor. If that’s you, then you should try to turn your portfolio (your assets) over as fast (as efficiently) as possible. The faster you can buy and sell 50 cent dollars, the higher your returns.

Again, simple math (this might be painfully obvious, but I’m still going to demonstrate):

Let’s say you buy a stock at $10 and you sell it at $20:

- If it takes 5 years to get from $10 to $20, you’ll earn a 15% CAGR on that invested capital

- If it takes 2 years to get from $10 to $20, you’ll earn a 41% CAGR on that invested capital

- If it takes 1 year to get from $10 to $20, you’ll earn 100% CAGR on that invested capital

In this case, your “profit margin” is the same in each case: it’s 100% in all three examples (the stock doubled in all three cases). However, your CAGR increases as your asset turnover increases—in other words, the more opportunities like this you can find and the faster they play out, the higher your portfolio returns will be.

So that demonstrates the various CAGR’s on the same level of profit margin. This is the same basic math that you’d see if you compare two companies with a 10% net margin, but Company A turns over its assets twice as fast as company B, then Company A’s ROA will be twice as high.

Now let’s quickly look at the same level of asset turnover on different levels of profitability:

Let’s say each year on January 1st, you buy one stock, and each year on December 31st, you sell it to buy something else:

- If the stock you bought goes up 15% over the course of the 1 year, obviously your CAGR is 15% on this 1 year investment

- If your stock goes up 25%, your CAGR is 25%, etc…

In this example, your asset turnover is exactly the same (you turn over your assets once per year in this case), but your profit margins are different.

Obvious stuff, right?

I think so, but I consistently read a lot of people referring to portfolio turnover as a bad thing, which runs counter to the math behind these examples.

Buffett’s Returns and Peter Lynch’s Famous 10-Baggers

It’s clear to see with these simple examples that portfolio returns (ROA) is dependent on two drivers:

- How much you make on each investment (profit margin)

- How quickly you can turn over your assets (asset turnover)

Buffett’s transition that Klarman referred to above is one where he transitioned over the course of his career from a lower profit margin, higher turnover investor to a higher margin, lower turnover investor. In the 50’s and 60’s, Buffett made many more investments, and made much smaller profits on average (in other words, he bought stocks, sold them when they appreciated to buy still more undervalued stocks). In the 80’s and 90’s, he began making fewer investments (due to increasing capital levels), but his profit margins grew (he went from making 20%-50% gains in shorter time periods to making 1000%+ gains over many years).

Interestingly, Buffett’s results (on a percentage return basis) were much better when he had higher turnover (and lower average profit per investment) in the early years than they are now. In fact, Buffett said his best decade of returns was the 1950’s, when he was making 50% annual returns, and investing in a variety of bargains and special situation events.

This wasn’t necessarily intended or by design, it was simply that Buffett was “taking what the defense gave him”. As his capital grew, he had to look for larger investments and had to extend his time horizon.

If he were investing again with $1 million or so, he’d be making many more investments and his asset turnover would be much, much higher—there is absolutely no doubt about this.

He may have a few investments that become big winners, but there would be very few 10 baggers, and many, many smaller, faster gains.

One other point that runs counterintuitive to what most people think: Peter Lynch is famous for the term “10-baggers”—investment that rise 10 times in value. But in fact, when Lynch started running the Magellan fund and was producing incredible 50%+ returns in the early years, his turnover exceeded 300% every year for the first 4 years (in other words, the average length of time he held a stock was only 4 months). I think in reality, his fantastic track record is much more because of higher portfolio turnover and much less because of the famous “10-baggers” that he cites in One Up on Wall Street.

Certainly profit margins are just as important a driver to profitability (portfolio returns), but I think turnover is vastly misunderstood.

I think it’s important when listening to the great investors–even Buffett–to keep in mind this math when you hear ubiquitous investment advice and generally accepted wisdom regarding turnover, investment time frames and holding periods.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at [email protected].