Outerwall is a stock that has been struggling as the cash flows from Red Box are drying up much faster than investors have expected. Not only that, but Outerwall management has had the troubling habit of throwing good money after bad by “investing” in things like ecoATM–kiosks that allow you to turn in your old cell phones for cash, a concept that doesn’t seem to be gaining traction.

This spending on business lines that were unlikely to succeed was all in an effort to extend the life of the company. Extending the life of a company is not always the best way to maximize value for shareholders. One thing I’ve observed is that dying businesses (or more euphemistically, businesses in “secular decline”) almost always turn out to be bad stock market investments. I think money can certainly be made from a cash cow like Red Box (even if the cash flow eventually will be $0), but not if the cash flow stream is attached to a public company. This is because of the inherent conflict of interest between a management team and the owners of the business. The owners of the business want to see the cash. The management team wants to continue getting a salary.

Of course, this is why activists have become so interested in Outerwall, and other companies that throw off copious amounts of cash.

Focusing on Stock Price vs. Running the Business

But here is a slightly different problem I’ve observed. Activists are much more interested in driving the stock price higher in the near term than they are in improving the long term value of the enterprise. A couple years ago, an activist (who failed in his attempt to get the company to sell itself) succeeded in driving the stock price of OUTR from around 60 to 80, where he was able to unload his stock. The stock now trades around 30.

After initially failing to get the company to sell itself, this activist was able to convince the company to take on a sizable amount debt to finance a massive share buyback program. This financial engineering tactic worked in getting the stock price up, but did the owners of the company (the shareholders who were left) benefit? Absolutely not. They loaded a dying business with massive debt, which hindered the ability of the company to deliver cash back to shareholders.

To me, this tactic of loading a company with debt to finance huge buybacks (in order to allow the activist to exit the stock at a (oftentimes short-lived) higher price) is not much different than the “greenmail” strategies that the activists used in the 1980’s.

I recently came across a video from a few years ago where Buffett was talking about Apple in 2013 when a few investors were pressing for Apple to return some of its massive cash to shareholders. Tim Cook had just recently taken over the reins from Steve Jobs, who always had a habit of ignorning Wall Street and focusing on the business at hand (a wise strategy for any executive). Buffett’s advice for Tim Cook was simply: Ignore the activists.

“The best thing you can with a business is run it well. If you run it well, the stock behaves fine over time… …I would run the business in such a manner as to create the most value over the next 5 or 10 years. You can’t run a business to try and run the stock up everyday.”

This is obviously the way Buffett has run his own business for the past 50 years. Despite 4 separate occasions where BRK dropped 50%, Buffett said: “We just kept focusing on building value.”

Wall Street’s Obsession with Buybacks

While I almost always think Buffett is spot on with his advice for management, it’s not necessary to always agree with his stock picks. Buffett also mentioned IBM in that interview. I noticed the share price of IBM was around $200 at that time and the share price of Apple was around $62 (split-adjusted). I looked at IBM a while back. Ironically, I felt that they were much more focused on pandering to Wall Street and the analyst community (with the previous management’s focus on share buybacks and the infamous “Road Map” that had a $20 EPS target that the current CEO finally promise-2014-10″ target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>had to walk back).

Buybacks are great in certain cases, but a management team who is trumpeting buybacks as a key business strategy is probably not entirely focused on running the business. Buybacks aren’t a business strategy, they are a capital allocation policy. Buybacks were an afterthought for Steve Jobs, and also for Warren Buffett himself. Buffett has mentioned buying back BRK stock here and there, but like Jobs, he was focused on running his business. I’m somewhat wary of CEO’s who are trumpeting buybacks and putting together glossy investor presentations that prioritize these capital allocation strategies above business strategies.

Now, I know buybacks are very popular among value investors. I too like buybacks, but buybacks don’t exist in a vacuum. Automatically and routinely using free cash flow to reduce share counts without any consideration given to price paid doesn’t automatically mean that value is being created. Like spending on R&D, marketing, capex, or any other capital allocation decision, buybacks don’t always create value. Companies often perform buybacks routinely as if it’s always value accretive. They would be much better off approaching it opportunistically, like when Jobs was considering it, or when Buffett talks about the price he would pay for Berkshire Hathaway shares. Buy it when it’s cheap, don’t just make buybacks a habit.

We obviously have the benefit of hindsight, and I am in no way making any predictions on IBM, but I will say that I think Apple was (and is) much more focused on running its business for the long-term than IBM is. Which is why I’m surprised that Buffett bought IBM.

Nevertheless, I think his general advice is—as usual—outstanding. Focus on running the business, don’t focus on the stock price.

I’d like to point out that David Einhorn was one of these activists back in 2013 calling for Apple to return cash. I respect Einhorn tremendously, and I wouldn’t put him in the category of activists who I consider modern day greenmailers. Einhorn is a much more thoughtful, much more owner-minded. He has engaged in activism, but is generally on the side of long-term shareholders (he himself has been a shareholder of Apple for a few years now).

And Apple did eventually institute a sizable buyback and dividend program, but in that case, it was probably warranted, and it didn’t come at the expense of marginalizing the balance sheet or distracting management from focusing on running the business.

Tying this All Together With Outerwall

It might be too late for Outerwall to correct its course, and because of the large debt, there are limited options to maximize the shrinking stream of cash flow. Ideally, the company would have focused solely on paying dividends to shareholders initially, running the business to maximize cash flow, keeping a clean balance sheet, and minimizing investments in long-shots. But again, management wants to keep their jobs and activists want a quick buck.

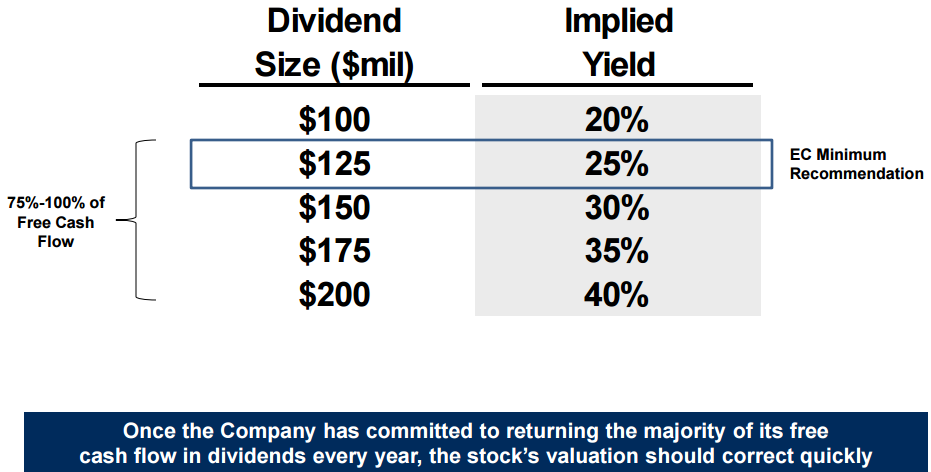

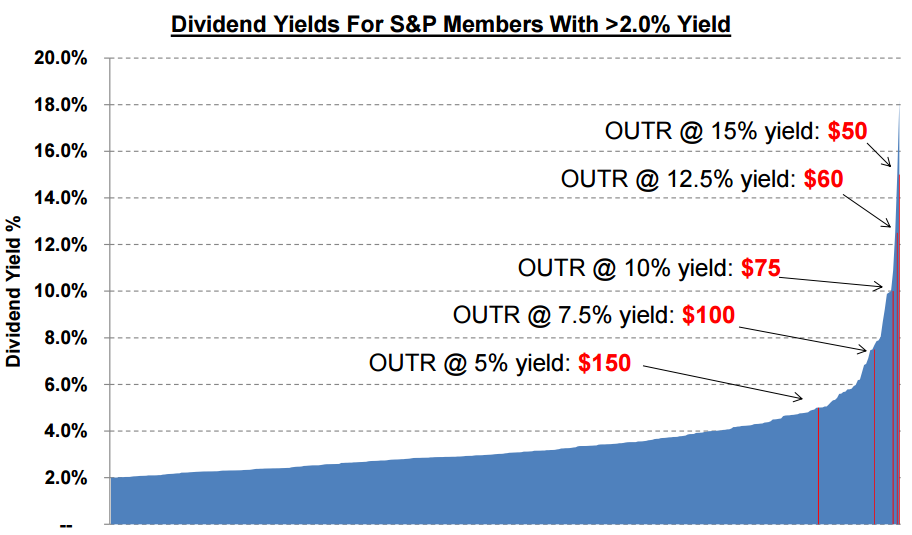

The latest activist in Outerwall (Engaged Capital) correctly points out that there is no law that says that buybacks automatically create shareholder value. They also correctly (in my opinion) point out that a business like Outerwall is much better in the hands of a private owner than in the public, because a private owner can cut costs, reduce debt, and allow the company to slowly die while siphoning off the still large (but declining) stream of cash flow. So these are good points. But then they have a few slides basically saying that if Outerwall paid a big dividend, the share price would skyrocket.

While I have nothing against short-term focused investors, I’d say the main objective for most activists is not improve business operations or create lasting value for shareholders, it’s to get the stock price higher as quickly as possible. As these slides point out, what could be quicker than simply declaring a massive dividend?

Maybe this works, but if it does I’m almost certain it will only accomplish what the previous activist investor did—get the stock price higher and dump the shares to another investor at a higher price (akin to greater fool theory). I personally find it to be a difficult game trying to get the timing right by jumping in and out of stocks. I’ve noticed the same arguments are being made for OUTR at $30 as were being made when OUTR was at $60. Maybe buying at $30 will allow you to sell out at $45. But those who bought at $60 using that same thesis are out of luck. So you have to a) know for sure there is a bottom, and b) time the bottom pretty accurately.

Also, one other point I would make is that dividends aren’t necessarily return on investment. Sometimes, they are return of investment (returns of principal). I understand that in this case, Outerwall is in fact generating sizable cash flows. But the cash flows are depleting. It’s not much different than an oil well that sees sizable cash flows in the first couple years followed by precipitous declines.

So a 10%, or even a 15-20% yield wouldn’t necessarily be unwarranted for a declining business. After all, if the denominator in the P/E ratio (or the numerator in the dividend yield) is declining rapidly, then the seemingly “cheap” ratios could be warranted or even not discounted enough. P/E’s of 3 aren’t necessarily cheap if multiple years’ worth of (declining) cash flow is needed to pay off debt.

Three General Takeaways

I don’t have a dog in the Outerwall fight. I have good friends (who are very smart investors) who have owned the stock in the past. Allan Mecham—an investor I respect tremendously—still owns (as far as I know) a large position. I think the best possible outcome (the only one I see resulting in profits) for shareholders is to get the company sold as quickly as possible. Let the private equity guys figure this out.

I do think watching this unfold in real time has been an excellent case study. There are specific things that could be discussed in much greater detail related specifically to the Outerwall situation, but my general takeaways:

- Rarely have I seen intrinsic value (long-term shareholder value) increased as a result of a company taking on massive debt to buy back stock. While it might successfully drive the stock price higher in the short term, in the long-term the debt—in the best case—takes a disproportionate share of the future cash flow away from shareholders, or—in the worst case—ends up compromising the financial condition and stability of the company.

- Shareholders are rewarded by companies with management teams who focus on running the business, rather than focusing on the stock price, or Wall Street demands, or short-term results.

- Seemingly cheap price to free cash flow valuations on companies with depleting streams of cash flows might make attractive private equity investments, but almost always make poor stock market investments due to the inherent conflict of interest between a management team and the owners (shareholders) of the business.

There are exceptions to these of course. One exception could be if the management team themselves happen to have ownership positions that dwarf their annual salaries/bonuses. But generally speaking, I have seen these three points hold true much more often than not.

Disclosure: Long AAPL, BRK-B

———

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

I established Saber as a personal investment vehicle that would allow me to manage outside investor capital alongside my own. I also write about investing at the blog Base Hit Investing.

I can be reached at [email protected].