I recently made a list of a few shareholder letters I want to read, and one that I completed a few days ago was Credit Acceptance Corp (CACC). This post is not a comprehensive review of the business, as I just started reading about the company. But I thought some readers might be interested in some initial notes.

(I am thinking about putting more of these “scratch notes” up as posts. If this is interesting to readers, please let me know. Often times, I read about a company and don’t end up coming to a solid conclusion. I have many pages of notes on companies that I don’t ever discuss, simply because the information might not be actionable currently. But if these types of notes are worth reading, then I’ll begin putting up more of them.)

Credit Acceptance Corp makes used-car loans to subprime borrowers. CACC has a different model than most used-car lenders. Instead of the typical subprime auto-lending arrangement where the dealer originates the loan and the lender buys the loan at a slight discount, CACC partners with the dealer by paying an up-front “advance” and then splitting the cash flows with the dealer after CACC recoups the advance plus some profit. The advance typically covers the dealer’s COGS and provides a slight profit, and CACC has a low risk position as it gets 100% of the loan cash flow until its advance is paid back. What’s left over gets split between CACC and the dealer. The bottom line is that the dealer gets less money up front, but has more potential upside from the loan payments if the loan performs well.

The model works like this (these are just general assumptions and round numbers to illustrate their model): Let’s say a used-car dealer prices a car at $10,000. Let’s say the dealer paid $8,000 for that car. The dealer finds a buyer willing to pay $10,000, but the buyer doesn’t have $10,000 in cash, has terrible credit, and can’t find conventional financing. CACC is willing to write this loan (CACC accepts virtually 100% of their loans). The buyer might pay $2,000 down, and CACC might send an advance to the dealer of around $7,000. So the dealer gets $9,000 up-front ($2,000 from the buyer and $7,000 from CACC). The dealer now has no risk, since it has received $9,000 for a car that cost it $8,000, and although the profit might be lower than if it got the full $10,000 retail value in cash, the dealer can make more money if the loan performs well. The $8,000 loan might carry an interest rate of 25% for a 4 year term, which is about $265 per month.

As the payments begin coming in, CACC gets 100% of the cash flow from the loan ($265 per month) until it gets its $7,000 advance paid back plus some profit (usually around 130% of the advance rate). Once this threshold is hit, if the loan is still performing, CACC continues to service the loan for around a 20% servicing fee, and the dealer keeps the other 80% of the cash flow as long as the payments keep coming in.

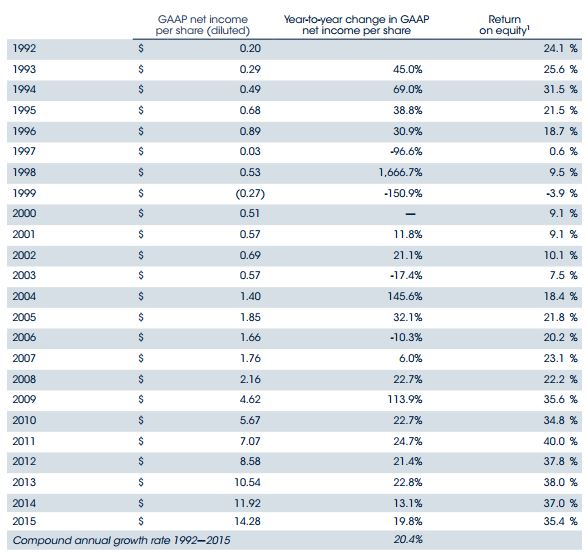

CACC has perfected this model and has achieved significant growth over time by steadily signing up more and more dealers. The result is a compounding machine:

But the conditions are always competitive in this business, and currently, lending terms are very loose and competition is brutal. But CACC is the largest in this space, and seems to be able to perform fairly well in periods of high competition by:

- Allowing volume per dealer to decline (fewer loans get originated at each dealer as CACC is willing to give up market share to competitors who are willing to provide loans at looser terms)

- Growing the number of dealers it does business with (developing more partnerships with new dealers helps offset the decline of business that is done at each dealership)

So overall, CACC has been able to grow volume consistently in good markets and bad markets by adding dealers to its platform. The company allows market share to decline during periods of high competition, and then when the cycle hardens (money tightens up), CACC is able to take back some of that market share.

Adding New Dealers Gets Harder

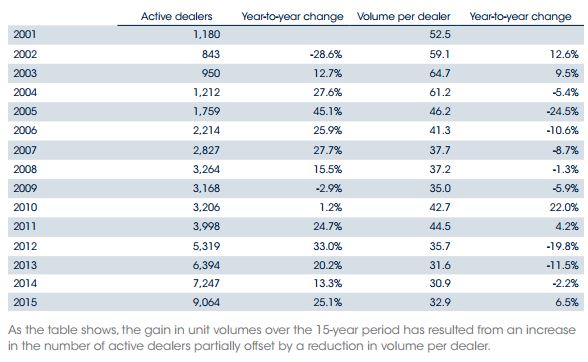

The problem is that CACC is now much bigger, and growing the number of dealers to offset the declines in volume that occur during soft markets is much more difficult. The company only had 950 dealers in 2003, which was the beginning of the last cycle. By 2007, the company had roughly 3,000 dealers. Dealers provide the company with customers. The ability to triple your potential customer footprint is extremely valuable as it allows you to lose significant market share at the dealership level and still write profitable loans at high returns on capital. Indeed, the company saw the number of loans per dealer decline by a whopping 41% during the soft (competitive) market cycle between 2003-2007. But during this time, its 3-fold increase in the number of dealers enabled overall volume to increase and earnings per share went from $0.57 to $1.76.

The market tightened up in 2007 (a good thing for companies like CACC because while economic conditions are difficult, higher cost competitors go out of business which makes life much easier for the remaining players). With a dealer count that was three times as large as it was just four years before, CACC could now focus on writing profitable loans and growing volume per dealer (i.e. taking back market share it lost at the individual dealership level).

The results are outstanding for a company that can successfully execute this approach, and CACC saw earnings rise from $1.76 in 2007 to $7.07 in 2011 thanks to a combination of growing profits and excess free cash flow that was used to buy back shares.

However, the cycle has gotten much more difficult again—starting in 2011 and continuing to the current time. CACC—to its credit—has continued to fight off competition by adding new dealerships (it has doubled its dealer count since 2011). But each year this becomes harder—CACC now has a whopping 9,000 dealers on its platform (nearly a 10-fold increase from 2003).

Competition is extremely tough currently, with dealers having the pick of the litter when it comes to offering finance options to its customers. CACC proudly states in its annual report: “We help change the lives of consumers who do not qualify for conventional automobile financing by helping them obtain quality transportation”. I think in the early years, this was true. Dealers could go to CACC for financing for its customers when no one else would lend money to that subprime borrower.

But CACC isn’t the only option currently, which means the terms CACC can demand are weaker. CACC used to write loans that were 24 months in the 1990’s. The average loan now has around a 50 month term. As competition heats up, dealers have more options as the third column in this table demonstrates:

CACC has grown mightily over the years, but since 2003 it has fought off a 50% decline in loans per dealer by dramatically growing the number of dealers it works with.

Can CACC Continue Compounding at the Same Rate?

The question for anyone looking at CACC at this level is whether the company can continue to perform well during increasingly competitive conditions. To produce attractive returns on invested capital going forward, the company needs one of two things to happen:

- Conditions need to worsen (higher interest rates, tighter monetary conditions) which will cause weaker competitors to exit the industry and lower the capital available to borrowers

- Absent better competitive conditions, CACC needs to be able to continue adding to its dealer count at a rate that more than offsets declines in loan volume per dealer

Thus far, the company has always been able to execute on the latter category. But it becomes harder and harder to move the needle as the company gets larger and larger. The company has 9,000 dealers and there are roughly 37,000 used-car dealerships in the US. So while growth is possible, a 10-fold increase in dealerships–which is what CACC has achieved since 2002–is no longer in the cards. I think the company will be much more dependent on the first category (competitive conditions) going forward, which unfortunately means they will be slightly less in control of their own destiny.

The hard part is trying to figure out when that cycle changes. And even when the cycle changes, I’m not sure that—short of a credit crisis—enough capital will leave to make life easy again for well-capitalized firms like CACC. Cycles will ebb and flow for sure, but there is a lot of data that points to how well auto loans performed during the credit crisis—which makes me think capital won’t flee the industry in a manner that many hope/expect.

Risks

The post is getting long, but I thought I’d briefly mention a few risks, which can be more thoroughly discussed in comments or another post.

One general risk is the regulatory risk as the CFPB has begun looking at subprime auto lenders. One related specific question I have asked myself while reading about CACC is this: why would the dealers agree to this model? Why would they accept a lower up-front cash payment (even with the potential added upside at the end of the loan term)? It doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. If you’re a dealer—why would you accept less cash up-front in the hopes that in 3 years you’ll begin to get some of that cash back from the dealer holdback (the amount that CACC splits with the dealer after it has been made whole)? You can likely maintain higher asset turnover and higher returns on capital by getting more cash up front and moving that money more quickly into new inventory than waiting 3-4 years for modest upside from interest payments.

I fear that there are two possible answers to why dealers participate in this structure. One reason could be because the dealers either can’t get this customer financing anywhere else (even from other subprime lenders–which means the customer is truly a bad credit risk by even subprime standards). The other possible reason is because dealers might be able to artificially inflate the price of the car above its fair market value–i.e. what a cash buyer or a buyer using traditional financing would pay for the car. If the car is only worth $12,000 but the dealer can get $14,000 by simply making sure the monthly payments are “affordable” (which is often the main point of concern for the typical subprime buyer), then the dealer can get an advance rate from CACC that is close enough to what the dealer would receive from one of the other traditional lenders or a cash buyer. This effectively gives the dealer nearly as much up front cash as well as the added kicker if the loan performs well. Meanwhile, the buyer overpays for a vehicle as a penalty for not being able to obtain traditional financing. That said, I don’t have evidence this is the case–but I am just posing these questions that crossed my mind as I read the 10-K, as I tried to put myself in the shoes of the dealers who willingly accept lower cash payments despite a seemingly unlimited array of options from other lenders.

One other aspect of this business that makes me uncomfortable is the very high default rates that exist across the subprime auto business. It is very hard to look through CACC’s annual report and get a clear answer on what the default rates really are, but they only collect about 67% of the overall loan values, which implies the average borrower quits paying 2/3rds of the way through the loan (it’s possible this number isn’t as bad as it appears since some cars might get sold, and the overall “loan value” includes projected principal and interest, but regardless–defaults rates are sky high). Looking at competitors like CRMT and NICK (which use more conventional provisioning methods)–reserves for credit losses are currently between 25-30% of revenues, and have risen dramatically in the previous five years or so.

Counteracting these risks are the fact that insiders have huge stakes in this company, and it does appear to be very well-managed business over a long period of time.

Brief Word on Valuation

It’s interesting how much higher CACC is valued than smaller (weaker competitors)—Nicholas Financial (NICK) is one I’ve followed casually to use one example. CACC is currently valued around $4 billion. For that, you get around $3.3 billion in net receivables and $1 billion of equity. NICK is roughly 10% of that size ($311 million receivables and $102 million equity), but has a market value of just $80 million. In other words, NICK has a price to book (P/B) ratio of 0.8 and CACC is priced at 4.0 P/B, or five times as expensive. Both have similar levels of debt relative to equity as well.

CACC gets much better returns on its equity than NICK, and so its valuation relative to earning power is only twice that of NICK’s (14 P/E at CACC vs 7 P/E at NICK). But I think given that they are competing for the same general customer, there is a pretty hefty premium baked into CACC’s shares.

I think CACC will likely do well regardless of how long these soft conditions last. And when the cycle hardens up, CACC has a large amount of dry powder available to cash and credit commitments that will allow it to fully take advantage of better lending conditions. But given the size of the company and the increased level of difficulty that they’ll face growing their footprint, I’m not necessarily sold on the current valuation in the stock, especially given the risks in a business like subprime auto lending.

To Sum It Up

They’ve done an impressive job of growing through the cycle by willingly ceding market share to preserve profits at the dealership level during competitive markets and offsetting this by increasing the number of dealers it works with. Now that they have over 9,000 dealers, it’s impossible to achieve the same level of growth going forward, and so the high returns on equity will be much more dependent on the level of profitability they can get with each loan, which will likely require some help from the competitive landscape. I think CACC remains quite profitable, but I don’t think they’ll see anywhere near the same rate of earning-power compounding going forward.

________________________________________________________________________________

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

John also writes about investing at the blog Base Hit Investing, and can be reached at [email protected].