Long time readers of the blog know that I’m a big sports fan, and occasionally I’ll use analogies from the sports world to make a point on investing. There are certain rules of thumb that I keep in mind when thinking about the public markets. There are certain principles, which are rooted in human psychology, that are almost guaranteed to create opportunities for rational minded investors over time. I keep a small list of “stock market truisms” as I call them—or recurring situations that present themselves over and over again in the markets, providing investors with opportunities to find mispriced merchandise.

One of these truisms is simply that stocks fluctuate (sometimes significantly) above and below their fair value at times. This is evident by looking at the 52 week high and low list. I read somewhere the average NYSE stock has an 80% gap between its yearly high and low price. The average NYSE company’s intrinsic value doesn’t change nearly this much in one year.

Similar to that principle, here is another one that I’ve always found very helpful to keep in mind:

- Markets tend to overemphasize the importance of events that just occurred. In other words, markets tend to overestimate the prospects of companies who have done well recently, and conversely tend to underestimate the prospects of companies that have done poorly recently.

So there will often be opportunities to find bargains among companies that missed quarterly expectations, or reported guidance that portrays a bleak picture for the coming quarter or even the coming year. Most of the investment community (analysts, bankers, portfolio managers)—despite what they might tell you—are very concerned with short term results and where the company (the stock) will go in the next few quarters. Even if a company will likely overcome its near term struggles, and will likely have earning power normalize in a couple years, portfolio managers will not feel compelled to own the stock if they think it will be “dead money” for the next 18 months.

Large Caps Get Mispriced As Well

Also, it’s important to note that this market truism applies to companies of all sizes. Some people acknowledge that small caps can get mispriced, but believe large caps are much more efficiently priced. That large caps are more efficiently priced might be true in general, but there are still glaring mispricings among even the largest stocks. Charlie Munger once mentioned that even though Coca Cola was one of the largest stocks in the S&P when Berkshire spent a billion dollars in the late 80’s to take a big position in the stock, it was still quite undervalued. It subsequently rose 10-fold over the following decade, netting Berkshire 26% annual returns on that investment over that time.

The largest stock in the market by market capitalization is Apple at roughly $650 billion. It just so happens that AAPL is up 42% in 2014, which means the market believes that Apple is worth nearly $200 billion more than it was on January 1st. 488 companies in the S&P 500 have valuations less than $200 billion—and that’s just the value that Apple has added to its market cap in 2014 alone. It’s unlikely the business is intrinsically worth $200 billion more than it was a year ago.

If we go back another 6 months to the middle of 2013, we see that Apple was valued closer to $325 billion. I’m not arguing whether Apple is overvalued now, undervalued now, undervalued 18 months ago, etc… I’m just saying that a year and a half ago it was valued around $325 billion, and now it is valued around $650 billion, and both of those valuations can’t be right. One of them is wrong—and likely wrong by a lot.

This is obvious to most of us—especially those of us familiar with Ben Graham’s simple foundation for value investing. Nevertheless, it’s always fun to point out the variance with which the market values its merchandise—and this is in a year that has not been very volatile at all (not one 10% correction in the S&P). These gaps between price and value get all the more prevalent in years where the overall market experiences volatility—which is one reason why as value investors, we root for volatility—it provides us with opportunity.

I mentioned earlier one reason that might explain this. Portfolio managers don’t want to own companies that they think will struggle for the next few quarters—even if they believe that the company will recover a year or two down the road. They can’t afford the career risk that comes with short term underperformance, and the perception is that a company with a negative near term outlook will be “dead money” for the next 18 months or so.

What I’ve learned through observation is that the 18 month “dead money” period for a lot of these stocks is often not nearly as long. But as a patient minded investor, you have to be willing to wait this long, or sometimes longer. Few investors have the ability to wait this long. The institutional imperative is quite strong—portfolio managers are judged based on quarterly and yearly results. Many of the greatest investors of all time have had periods of time (sometimes even a few years) of underperformance. This type of period is almost always followed by periods of significant outperformance, but few investors are willing to wait for the end result. And this leads to constant activity, and constant movement, which creates buying and selling decisions that are not based on the long term earning power and the long term value of the company and security in question.

Mispricings Occur When Human Reactions Are Involved

The reason that these market mispricing situations continue to occur is simply because of human nature. That’s the reason I’m confident that there will always be opportunities for patient minded value investors. It’s hard to fight human nature. One glaring example in the sports world currently is the New England Patriots. As much as it pains me to say this (being a fan of a different AFC East team), the Patriots are one of the best run franchises in sports from the front office to the coaching staff to the quality and work ethic of the players themselves. And of course, they have one of the greatest quarterbacks of all-time leading the way for them.

But all of this was forgotten just a couple months ago when New England was blown out by Kansas City and fell to 2-2 on the season. The talk that week in the NFL was that the Patriots’ time in the sun had come to an end. Belichick no longer had his “genius” touch, Brady was a shadow of his former self as a QB, the team lacked cohesiveness at various positions, etc… Basically, the Pats were getting written off completely, just 4 weeks into the season.

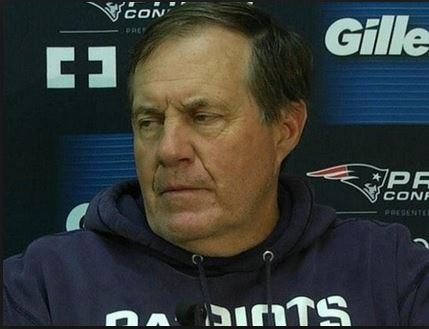

I found this post-game exchange (or lack thereof) between Belichick and a reporter comical. Brady played terrible against the Chiefs, and since the game was out of hand, the Pats decided to give their backup QB some playing time. Somehow, this apparently was taken by some as a possible harbinger of what might come (quarterback controversy in New England). The picture below says it all. It’s the look Belichick gave the reporter who asked whether it might be time to “evaluate the quarterback position”:

Since this interview, the Pats have gone 8-1 (losing only to the hottest team in the NFC—the Green Bay Packers), and everything from week four has been forgotten.

As a side note, this same human nature phenomenon was exemplified with the Packers, who also got off to a slow start which caused unrest among Packer fans, and prompted QB Aaron Rodgers now famous quip “I’ve got five letters for Packer fans: R-E-L-A-X… Relax”.

If only the New England Patriots were publicly traded as an MLP, like the Boston Celtics used to be!

The stock in both the Packers and Patriots would almost certainly have been marked down in late September, only to have soared right back two months later when the fears subsided.

Football fans and sports media members—just like stock market participants—tend to overemphasize the relevance of short term results. And this causes inaccurate assumptions and valuations, and leads to irrational decision making.

The reason is that football fans, media members, and stock market participants are humans. And humans are prone to behaving in a particular way. Although our reactions are unpredictable in the short term, there are certain patterns that we are destined to repeat over and over again.

I just read the book “The Great Crash: 1929” and it’s a great book that highlights some of these behavioral traits that occurred in 1929—and again in virtually every other bubble since.

But while very occasionally these behaviors spread to the entire public at large causing market wide mispricings of epic proportions (bubbles and crashes), they occur far more frequently on a smaller, more specific case at the individual stock level.

I think it helps to keep an eye out for the media member who is asking about whether it’s time to think about starting Jimmy Garoppolo over Tom Brady. When these types of questions are getting asked, there is often a mispricing and a subsequent opportunity.