“Our financial goals are to earn consistent underwriting profits and superior investment returns to build shareholder value” – Markel 2013 Annual Report

Markel is an outstanding business currently in its 85th year of operations. It is an excellent insurance company with a history of underwriting profits. It is also a superb investment company with a history of above average investment returns. Markel had an outstanding year in 2013, basically doubling the size of its insurance business and investment portfolio in an acquisition that the market hasn’t seemed to fully value yet. I think the shares are priced not just fairly—but cheaply—at a valuation level where investors have the chance to partner with one of the great long term compounding machines of the past 3 decades and achieve investment results for a long period of time that will at least equal—and possibly exceed the comprehensive returns on equity and growth in book value that the business achieves.

I’ll discuss my opinions on Markel, but first a quick overview of the fundamentals inherent to the Property and Casualty insurance industry, for those who need a quick primer. For those that don’t, feel free to skip ahead…

Insurance—Desirable Business Model Leads to Subpar Returns

Insurance companies have a unique feature that most businesses lack. Most businesses have one main source of capital to invest—namely the capital that the shareholders invested into the business. But Markel—and other insurance companies—have two:

- Shareholder Equity

- Reserves from Policyholders

Insurance companies have the added benefit of being able to accept money from customers (premiums) long in advance of the requirement to pay for the losses associated with that revenue (claims).

Of course, this concept is referred to as float—or the policyholders’ money that an insurance company gets to invest after receiving the premiums but before paying the claims.

Buffett made this concept famous, and he describes it often in his letters—here is his quick explanation in the most recent annual report:

“Property casualty insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later… This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums—money we call “float”—that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume.”

Although technically a liability, float is really an incredibly valuable asset—so much so that the industry at large is willing to lose money on underwriting in exchange for the access to this float. The concept is somewhat similar to a bank that collects deposits at a cost of say 3% and invests or lends those deposits out at say 6%–profiting from the 3% spread. Unlike banking however, it is possible for insurance companies to reduce their cost of float down to zero—or in rare cases even below zero cost. In other words, instead of having to pay 3% to gather funds, some insurance companies actually breakeven on their underwriting, meaning that this float is effectively “free”—like a bank that has no costs associated with gathering deposits.

Breaking even on the underwriting might not sound like a terrific situation, but it actually is quite valuable in the insurance business, as it effectively allows the business to use other peoples’ money to invest for its sole benefit. It’s effectively like taking on a partner who supplies your business with capital but asks for no equity stake nor charges you any interest—effectively this breakeven result creates an interest free loan for the insurance company.

In some rare situations, an insurance company not only breaks even on the underwriting, but actually makes consistent profits. This pleasant situation results in two possible streams of income:

- Underwriting profits

- Investment profits

The company in this rare situation actually gets paid to hold and invest their policyholders’ funds—like a bank that somehow charged depositors interest for the privilege of keeping their money at the bank.

Insurance—Competition Creates Mediocre Returns

Unfortunately for insurance companies, the nature of capitalism is such that this valuable business model combined with relatively low barriers-to-entry creates intense competition in the industry. Each insurance company understands how valuable this float is, and so they fiercely compete for a piece of the industry’s premium volume and the float that accompanies it.

This intense competition leads to companies being very willing to write business at a loss just to access this valuable float. These factors have led to very mediocre returns on equity over time for the industry as a whole.

Buffett again:

“Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous in most years that it causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. For example, State Farm, by far the country’s largest insurer and a well-managed company besides, incurred an underwriting loss in nine of the twelve years ending in 2012… Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry—despite the float income all companies enjoy—will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns as compared to other businesses.”

The P&C insurance industry has long operated at a combined ratio well over 100—meaning collectively insurance companies lose money on their underwriting. The combined ratio measures the total insurance costs (expenses and claims) as a percentage of premiums. A combined ratio of 100 is breakeven—meaning that the total expenses equaled premiums. Over 100 is an underwriting loss, below 100 signals an underwriting profit.

Moats in a No-Moat Industry

But some businesses—Berkshire certainly being one—have carved out competitive advantages in this cyclical industry with commodity-like economics. Some businesses are able to consistently operate at an underwriting profit, which creates enormous value for shareholders over time. When combined with good investment skills, this combination can create an incredible compounding effect.

How do insurance companies create this advantage?

There are a few answers to that question, but one major factor is the willingness to walk away from business that will not result in profits. This is harder than it sounds, because it involves willingly lowering current revenue—something that most executives and almost all Wall Street analysts don’t like. But companies that are able to actually reduce their underwriting volume during soft markets are able to preserve their capital and their profitability. Every insurance company understands this, but few are willing to walk away from business. It is difficult for executives of insurance companies to willingly shrink their revenues when their competitors are growing theirs. It is also difficult for insurance employees—who are paid on commission in some cases—to willingly walk away from current business—even if it is the best thing to do for the long term interests of shareholders and employees.

However, a select few businesses have created incentive structures and an owners’ minded culture that allows them to be able to operate in such a profitable manner.

Berkshire obviously is one example of this—compounding shareholder value at 20% annually for half a century.

Markel is another example.

Introduction to Markel—A Value Compounding Machine

Markel was founded in 1930 and initially focused on insuring taxi cabs in Norfolk, Virgina. It was a family owned and operated business for decades until it went public in 1986, but even to this day it has largely maintained its culture as a family run business.

Markel is a compounding machine. It has grown book value by 20.1% per year since its IPO in 1986, thanks to three main ingredients:

- Consistent Underwriting Profits

- Superior Investment Results

- Excellent Long-term Owner/Managers

The three pronged approach has resulted in enormous shareholder value creation over time, even when compared to better-known compounders such as Berkshire Hathaway.

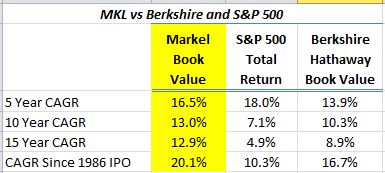

Here are the results of Markel’s per share book value compound annual returns vs those of Berkshire and the S&P 500:

As the compounding of book value goes, so goes intrinsic value and so goes the stock price. MKL’s stock price has compounded at 17.1% over 27 years since the IPO, turning a $10,000 investment in 1986 into $705,596 in 2013:

I like to think about Markel as a holding company with three distinct business lines:

- Insurance

- Investments

- Operating Businesses (Markel Ventures)

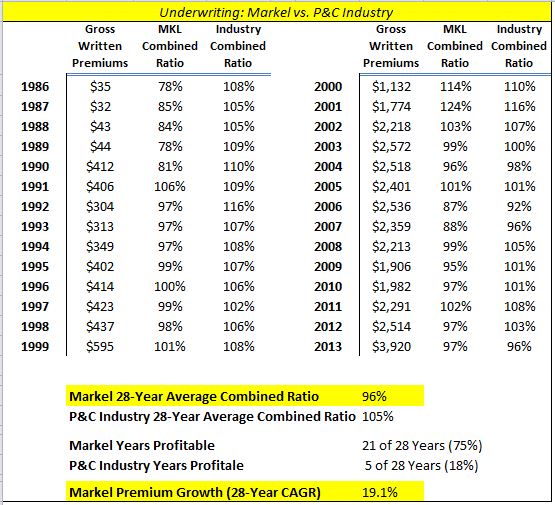

Markel is a very disciplined underwriter with a history of underwriting profits (Markel’s 28 year average combined ratio is an incredible 96%). This profitability is as rare as it is valuable in the insurance business. It provides Markel with cash flow from insurance operations, but more importantly, it means that the float—the money that belongs to policyholders from premiums that are reserved for future claims—is effectively free money for Markel to invest for the sole benefit of shareholders. It’s like a massive loan that bears no interest and doesn’t have to be paid back!

As long as Markel remains a profitable underwriter over time, it will have two main buckets of permanent capital to invest:

- Float

- Shareholders’ Equity

The former is conservatively allocated to mostly short duration fixed income securities—bonds. The latter is invested in long term securities—namely stocks. Markel invests a much larger portion of its equity into stocks relative to most P/C insurance companies. This means higher returns for the investment portfolio over time, and it means above average book value compounding, which correlates over time with the intrinsic growth in value of the enterprise.

It also means slightly more volatility—which is probably why most insurance companies prefer not to own equities. But Markel’s logic is the same as Buffett’s and most value investors—volatility is not risk. Risk is the uncertainty of losing permanent capital—not the temporary fluctuation in the quoted value of that capital.

I’m surprised that after 49 years of 20% annual returns at Berkshire Hathaway that more companies don’t follow this relatively simple model.

Not Just Stocks & Bonds, but Businesses—Markel Ventures

In addition to stocks and bonds, Markel also allocates capital to privately owned businesses. The company recently established an entity called Markel Ventures, which is the vehicle that holds wholly-owned and partially-owned operating businesses.

Markel Ventures is only a very small piece of the overall Markel pie, but it is rapidly expanding—revenues grew 40% last year as new businesses were acquired. I believe this will be a significant source of value for Markel in years to come as the vehicle begins to throw off greater and greater free cash flow for Markel to reinvest.

Markel invests in businesses using the same principles it uses to buy stocks—similar to how Buffett thinks about investing in public and private businesses.

So how does an insurance company—a business in an industry known for subpar returns—create above average returns on equity and high book value compounding over three decades?

Competitive Advantages at Markel

Markel is unique—an insurance company with various competitive advantages. A few of these advantages are:

- Long-term Owner-Minded Management—Markel’s managers are experienced, disciplined, and very conservative in their underwriting, investing, and reserve policies.

- Culture—management has established and maintained a culture that promotes long term oriented thinking in every aspect of their business that benefits shareholders, customers, and employees.

- Niche Insurance Markets—it has specialized expertise in markets where many other insurance companies don’t write

- Size—it is one of the largest players in its markets with a long term history—which gives it scale advantages as well as customer loyalty (customers in these hard-to-place risk categories know Markel is one of the largest and most secure counterparties in their markets)

- Disciplined and Profitable Underwriting—willing to shrink premium volume in soft markets

- Superior Investment Skills—Tom Gayner is a high quality value investor and Markel allocates a larger percentage of its shareholder equity (i.e. permanent capital) to equities than most other insurance companies

Let’s explore a few of these advantages that have carved out Markel’s ever widening moat over the years…

Competitive Advantage #1: Management and the Markel Culture

“One of the primary reasons for (our) success is that we have a large group with a long tenure… Another important fact is that all Markel associates own stock in the Company, and many have very significant investments.” –1997 Shareholder Letter

Markel’s history goes back to the 1930’s when the company was founded. For most of its history, the business was family owned and controlled. It went public in 1986 to provide liquidity for some of the cousins and other relatives who were not interested in owning an insurance company, but the principles of the Markel family are very much intact today.

These principles—honesty, integrity, customer service, and work ethic among others—can be evidenced by listening to management and observing their behavior over long periods of time. I’ve gone through every shareholder letter since the IPO in 1986, and it is very clear that they put a top priority on maintaining the culture that the founding family established decades ago.

This type of qualitative analysis is often deemphasized, and this type of rhetoric is common at almost every company. But at Markel, this isn’t just rhetoric—it is how they actually run their business. And this culture creates a competitive advantage for a few reasons, but one is that employees think like owners—and they operate with the long term in mind.

Many of the letters from the 1980’s are written by executives that still are at the company playing a major role today. Employee turnover is very low. This means that executives are given the freedom to think beyond quarterly, yearly, or even 2-3 year results. They are thinking 5, 10, even 20 years down the road. They own stock in their company, and their compensation is highly tied to long term incentives such as 5-year CAGR of book value. Employees at lower levels are also incentivized this way—underwriters are not incentivized to write business at any price—they are incentivized to write profitable business.

This creates a culture of owners working together to build value.

Competitive Advantage #2: Niche Markets

“By focusing on market niches where we have underwriting expertise, we seek to earn consistent underwriting profits, which are a key component of our strategy. We believe that the ability to achieve consistent underwriting profits demonstrates knowledge and expertise, commitment to superior customer service, and the ability to manage insurance risk.” –2013 Annual Report

Warren Buffett mentioned at a recent shareholder meeting that one of Berkshire’s huge competitive advantages is that they have no competitors in certain activities they engage in. Markel’s insurance business is founded on hard-to-place risks, which by definition are lines of insurance that relatively few insurance companies participate in.

This means they insure things that other insurance companies don’t. Throughout its history, Markel has indeed insured such unusual risks such as classic cars, boats, event cancellations, children’s summer camps, horses, vacant properties, new medical devices, and even things such as the red slippers Judy Garland wore in the Wizard of Oz.

Markel has specialized in these niche markets for decades, and has built up both experience and a brand name among customers and prospective customers as one of the largest players in these specialty markets. Their size, their expertise, and their capacity to insure these risks that others won’t have given Markel a sizeable advantage over competitors. Most don’t want to compete in these lines. Those that do try to enter these lines often lack have the specialized knowledge that Markel has built up over time.

Competitive Advantage #3: Disciplined Underwriting

“In tough markets, we will need to be extremely disciplined and willing to walk away from underpriced business” –2013 Shareholder Letter

This has been the philosophy at Markel for three quarters of a century. And it’s not just ubiquitous rhetoric that you hear from most P&C management teams—the results show Markel management “walks the walk” as well, producing remarkable results relative to the overall P&C insurance industry:

These are incredible underwriting results, especially when taking into account the enormous growth in premiums that Markel has achieved over the years. Growth in premiums often do not equate to growth in per share intrinsic value, but as management said in the 2013 Shareholder Letter:

“Our compensation as senior managers, and our wealth as shareholders of the company, depends on profitable revenues, not just revenues. That said, when it comes to profitable revenues, more is better.”

Competitive Advantage #4: Equity Investing

“We have a larger portion of our portfolio allocated to common equities than many property/casualty insurance companies. Although we recognize the short term impact (of higher volatility), we are confident our strategy will enhance shareholder value in the long term.” –1992 Shareholder Letter

Like value investors, Markel believes that equating volatility with risk is nonsensical. They look at their shareholders’ equity as permanent capital, which implies that they can invest that capital with a long term view, and their philosophy is that stocks—specifically quality companies at fair prices—will outperform bonds over long periods of time.

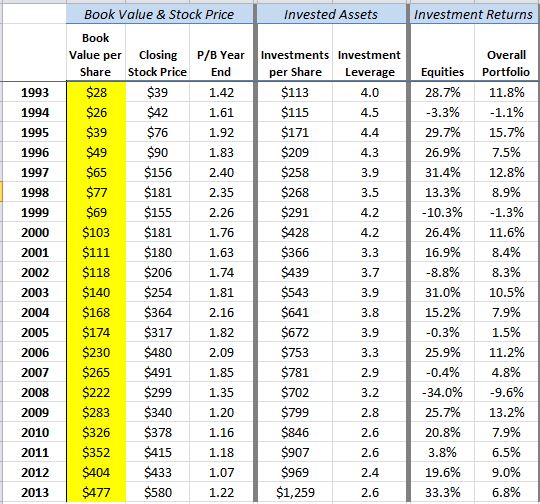

This strategy has worked. Here is a look at the average annual returns that the investment portfolio has produced—with a side by side comparison of the steadily rising increasing value as shown in the per share book value and stock price:

Tom Gayner, Markel’s CIO, runs the investment portfolio, and is a well-known student of value investing and the principles of Warren Buffett. Gayner’s equity results would put him in the top 10% of just about any mutual fund category.

Gayner invests in equities using a simple four point filtering process that is rooted in the principles of value investing. He likes to look for:

- Profitable companies that produce high returns on capital

- Management that is both talented and honest

- Businesses that have sizable reinvestment opportunities (compounding machines)

- A fair price

Although the level of performance might not seem to rank him among other superinvestors, it certainly adds enormous value when combined with the structural advantage of negative cost float (“better-than-free” leverage) that Markel uses.

Superior Investments Results + Zero-Cost Leverage (Float) = Outstanding ROE

For example, at the end of 2013, Markel had investments $1,259 per share, and net investments (after subtracting all debt) of $1,098 per share. They also had leverage (investment assets/equity) of 2.6—which happens to be well below Markel’s historical leverage level.

This leverage means that if Markel’s overall portfolio averages 5.0% after tax, the portfolio will gain $63 per share, which represents 13.2% of book value. If leverage increases to a level of 3.0 invested assets to equity (historical average is 3.5), then the contribution to ROE from the investment portfolio gets to 15%. Because of Markel’s consistent ability to produce underwriting profits as well as a growing revenue stream from Markel Ventures, these investment results can be thought of as a “back of the envelope” conservative proxy for comprehensive ROE and book value growth.

Another “back of the envelope” way to look at it: if Markel can produce breakeven underwriting results (including interest charges) and can produce 5% after-tax investment returns, then Markel is priced at around 9 times comprehensive earnings ($595/$63 comprehensive EPS: basically the change in equity which includes income as well as unrealized gains on investments that bypass the income statement).

Of course, leverage works in both directions, but thanks to Markel’s underwriting practice and long-term orientation, their lumpier than normal earnings will likely lead to far superior value creation over time.

When discussing this “leverage”, remember—As long as Markel underwrites profitably over time, this “leverage” provides capital that is both free and permanent. Markel’s overall balance sheet is very conservatively capitalized, with a debt to equity ratio of around 34%.

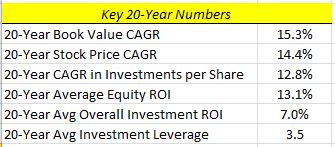

Over the past 20 years, Markel has produced pretax average annual investment returns—in both stocks (13.1%) and its overall portfolio (7.0%)—that far exceed the investment returns that most P&C companies achieved over that period of time. Much of this has to do with outstanding stock investing.

As Gayner said in the recent shareholder letter:

“Our equity portfolio has added immense value to our total returns over many years and we think our long standing and consistent commitment to disciplined equity investing is a unique and valuable feature.”

Alterra Acquisition and Equity Allocation

Markel acquired Alterra on May 1st, 2013. The company is referring to this merger as “transformational” as it not only nearly doubled the insurance business, but also increased the size of the investment portfolio from $9.3 billion to $17.6 billion.

The acquisition not only increased the size of the investment portfolio, but also significantly altered the allocation profile between stocks and bonds. At year end, Markel had just 17% of its portfolio in stocks, vs. around 25% a year ago.

Put differently, Markel had just 49% of its shareholder equity invested in stocks, compared to a management stated target of around 80%.

As Gayner said on the 2nd Quarter 2013 Conference Call:

“The addition of the Alterra portfolio was a sluggish (reallocation of investments), and it is appropriate for you to assume that we will methodically and opportunistically guide the equity investment percentage back up to the historical levels over time.”

This reallocation will be a catalyst for sizable increases in Markel’s investment returns, ROE, and book value over time.

Bringing It Together—Great Company, Great Price

“At Markel, underwriting and investing are working from the same blueprint. The principles that support profitable underwriting are the same ones that lead us to superior investment returns and, in turn, help us build shareholder value. These important principles are: maintaining a long-term time horizon, discipline, and continuous learning.” –2006 Shareholder Letter

The thesis really boils down to the fact that we have a great business that has compounded book value at 20% annually since its IPO thanks to the following key attributes:

- Long term owner friendly managers

- Profitable, conservative insurance operations

- Superior investing results

Markel is a compounding machine and should be able to continue to replicate this formula for years into the future.

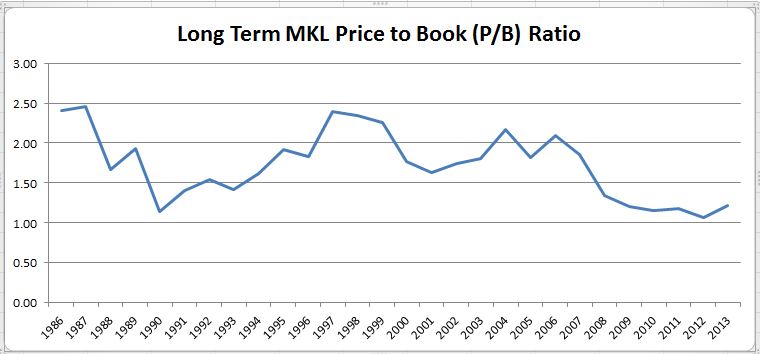

And to add a cherry on top, the stock is actually priced cheaply relative to normalized earnings and Markel’s own historical price to book ratio:

- Markel’s current P/B Ratio: 1.24

- Markel’s long-term average P/B Ratio: 1.73

The low price is surprising considering how well the company is positioned to grow its insurance operations, investment portfolio, and private business holdings via Markel Ventures.

The price to book (P/B) ratio is at the very low end of the 28-year range:

So the current valuation is just 71% of the long term average valuation and don’t forget, the denominator in this multiple has grown at 20.1% per year since 1986!

I believe Markel is an outstanding opportunity—with or without multiple expansion. So I think the long term business prospects are much more important to consider than short term catalysts, but I do think that the reallocation of Alterra’s portfolio along with Markel’s strength to take advantage of the inevitable return to a hard insurance market will provide a tailwind to the current valuation.

To illustrate the power of compounding, let’s assume book value grows at rates between 10-14% annually over the next 5-10 years (significantly lower than Markel’s long term historical range). Let’s also assume a valuation multiple between 1.5 (also conservative vs. long term average of 1.73 P/B ratio):

- Book Value Grows at 10%

- Book Value in 5-10 Years = $768 to $1,237

- Stock Price at P/B of 1.5 = $1,152 to $1,856

- Stock Price CAGR in 5-10 Years: 12.0% to 14.1%

- Book Value Grows at 14%

- Book Value in 5-10 Years = $918 to $1,768

- Stock Price at P/B of 1.5 = $1,452 to $2,652

- Stock Price CAGR in 5-10 Years: 16.1% to 19.5%

I think there are arguments to be made for higher compounding as well as higher valuations, but I think these are reasonable possibilities.

To Sum It Up

With Markel, we get:

- Consistently profitable insurance company

- Superior investment holding company

- Shareholder friendly long term management

- Cheap Price

On 3/31/13, MKL trades at $595 per share. The stock is trading at the very low end of the historical valuation range at 1.2 times book. This seems far too cheap for a company of this quality—one that has compounded book value per share at 20.1% since its IPO in 1986.

So we have a great business—and an opportunistic investment. A compounding machine that is growing intrinsic value at greater than 15% annually—available at a price that allows investors to experience an investment result that should equal—or possibly exceed—the internal business returns over the next 5-10 years.

Disclosure: John Huber owns shares of MKL in his own account and in accounts he manages for clients.

_____________________________________________________________________________

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, dressme.co.nz/ball-dresses.html”>LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

John also writes about investing at the blog Base Hit Investing, and can be reached at [email protected].