I recently read Annie Duke’s book on decision making called Thinking In Bets. One of her main points is that life is like poker and not chess. In chess, the superior player will always beat the inferior player unless the better player makes a mistake. There is always the correct move to make, and the correct move in every situation in the game is potentially knowable, and so chess is about pattern recognition — memorizing as many sequences as possible and then being able to draw on this library of potential moves during the game.

The best players have the deepest database of chess moves memorized and the best ability to access them quickly. Absent the very rare unforced mistake, an amateur has essentially no chance to beat a grandmaster who in some cases has as many as 100,000 different board configurations memorized (along with the correct move for each one).

However, life isn’t like chess, it’s like poker. In poker there are lots of uncertainties, an element of chance, and a changing set of variables that impact the outcome. The best poker player in the world can lose to an amateur (and often enough does) even without making any poor decisions, which is an outcome that would never happen in chess.

In other words, a poker player can make all the correct decisions during the game and still lose through bad luck.

One of my favorite examples that Duke uses in the book to illustrate the idea of good decision but unlucky outcome was Pete Carrol. The Seahawks coach, needing a touchdown to win the Super Bowl with under a minute to go, decided to pass on 2nd & goal from the 1-yard line instead of running with Marshawn Lynch. The pass got intercepted, the Seahawks lost and the play was immediately and universally derided as “the worst play call in Super Bowl history“.

But Carrol’s play call had sound logic: an incomplete pass would have stopped the clock and given the Seahawks two chances to run with Lynch for a game winning score. Also, the odds were very much in Carrol’s favor. Of the 66 passes from the 1 yard line that season, none ended in interceptions, and over the previous full 15 seasons with a much larger sample size, just 2% of throws from the 1 yard line got picked.

So it arguably was the correct decision but an unlucky outcome.

Duke refers to our human nature of using outcomes to determine the quality of the decisions as “resulting”. She points out how we often link great decisions to great results and poor decisions to bad results.

Decision-Making Review

The book prompted me to go back and review a number of investment decisions I’ve made in recent years, and to try and reassess what went right and what went wrong using a fresh look to determine if I’ve been “resulting” at all.

I reviewed a lot of decisions recently, but I’ll highlight a simple one and use Google as an example here.

I was a shareholder of Google for a number of years but decided to sell the stock last year. After reviewing my investment journal, I can point to three main reasons for selling:

- Opportunity costs — I had a few other ideas I found more attractive at the time

- Lost confidence that management would stop the excess spending on moonshot bets

- I was seeing so many ads in Youtube that I felt like they could be overstuffing the platform and therefore alienating users (I still think this could be a risk)

I think the 1st reason was my strongest logic, and while a year is too short of a period to judge, I think what I replaced Google with has a chance of being net additive over the long run.

However, as I review the journal, my primary motivation for selling Google wasn’t opportunity costs and there were other stocks that could have been used as a funding source for the new idea(s). The main reasons for selling Google was I lost confidence that management would ultimately stem unproductive spending and I was getting increasingly concerned about the pervasive ad load on YouTube.

Expenses

Google Search is a massively profitable asset with probably 60% incremental margins that has always been used to fund growth initiatives. Some of these investments earn very high returns with tighter feedback loops and clear objectives. Building new datacenters to support the huge opportunity in front of Google Cloud or the rapidly growing engagement on YouTube has clear rationale. Hiring smart engineers to work on AI technology has a longer feedback loop but is just as important. But some of the moonshot bets seemed to me like money going down the drain with no clear path toward ever earning any real return. I felt this was diluting the value of the huge pile of cash flow. My thesis was that this would eventually change, but I began losing confidence that it would.

But only a year later, operating expenses have flatlined and have begun falling as a percentage of revenue, and buybacks are rising quickly and I think will prove to be a great return on investment at the current share price.

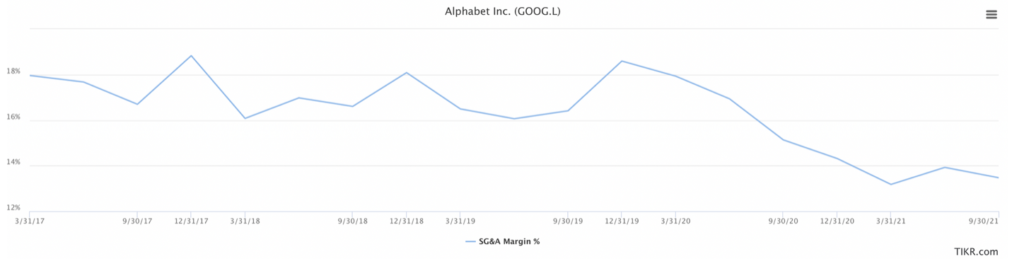

I’ve been watching operating expenses flatline, and SG&A is falling as a percentage of revenue:

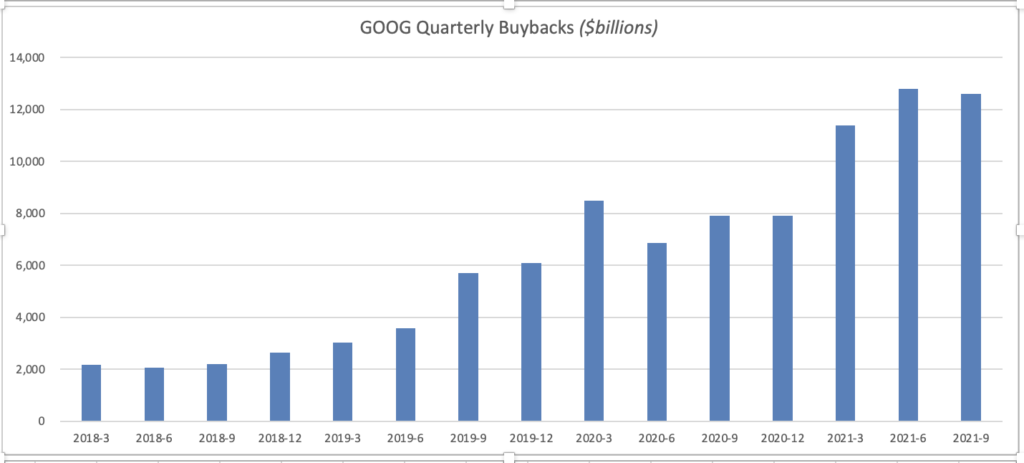

Covid has been a tailwind to Google generally, but one benefit that I don’t see talked about is how shocks like Covid tend to drive more focus on core strengths. Crises tend to be tailwinds to future cost efficiencies. I read press releases on a weekly basis last year about companies selling “non-core assets” (why they’d purchase non-core assets in the first place is a question I’ve never figured out). Soul searching tends to happen during bad times and the best companies come out of a crisis in better shape, like an athlete that is more fit. Google was far from unfit prior to Covid, but it’s possible that their leadership emerged more focused. The moonshot investments haven’t stopped, but buybacks have increased dramatically during the pandemic:

This alone will be a significant tailwind to value per share going forward.

After reviewing my spending concerns, I chalk it up to a bad outcome (for me as a seller of the stock) but not necessarily a poor decision. The facts changed (management in my view has improved focus on capital allocation) and so I will change my mind.

However, I spent the most time thinking about the final reason (YouTube ad load) and here is where I think I made a bad decision. Fortunately this little post-mortem exercise led to a framework that I think will help my process.

Flaws You Can Live With vs. Catastrophe Risk

My friend Rishi Gosalia (who happens to work at Google) and I were exchanging messages Saturday morning and he made a comment that I spent the whole weekend thinking about:

“Investing is not just knowing the flaws; it’s knowing whether the flaws are significant enough that I cannot live with them.”

I thought this was an excellent heuristic to have in mind when weighing a company’s pros and cons. Alice Shroeder once talked about how Buffett would so quickly eliminate investment ideas that had what he called “catastrophe risk”. I wrote about this framework way back in 2013, and it has always been a part of my investment process. I still think it’s a critical way to evaluate businesses because many investment mistakes come from overestimating the strength of a moat. Conversely, nearly every great long term compounder is a result not necessarily from the fastest growth rate but from the most durable growth — the best stocks come from companies that can last a long time.

Thinking critically about what could kill a business has on balance been a huge help to my stock picking. But, my chat with Rishi made me realize this emphasis on cat risk also has a drawback, and I began thinking about numerous situations where I conflated known and obvious (but not existential) flaws with cat risk, and this has been costly.

I think this is one aspect of my investment process that can and will be improved going forward. Much thanks to Rishi for being the catalyst here.

Google Firing on All Cylinders

Google has in my view one of the top 3 moats in the world. The company aggregates the world’s information in the most efficient way that gets better as its scale grows, and it has the network effect to monetize that information at very high margins and with very low marginal costs. Google might be the greatest combination of technology + business success the world has ever seen. My friend Saurabh Madaan (a fellow investor and former Google data scientist) put it best: Google takes a toll on the world’s information like MasterCard takes a toll on the world’s commerce. This information over time is certain to grow and the need to organize it should remain in high demand.

Google’s revenues have exploded higher as brand advertising spending has recovered from its pandemic pause, engagement on Youtube continues to be very strong and ad budgets in some of Google’s key verticals like travel have also rebounded.

The most growth could come from the monster tailwind of cloud computing. Google will benefit from the continued shift of IT spending toward infrastructure-as-a-service (renting computing power and storage from Google instead of owning your own hardware). Google excels in data science and they have the expertise and technology that I think will become increasingly more valuable as companies use AI to improve efficiency and drive more sales.

Google could also see additional tailwinds from one of the more exciting new trends called “edge computing”, which is a more distributed form of compute that places servers much closer to end users. “The edge” has become a buzzword at every major cloud provider, but the architecture is necessary for the next wave of connected devices (Internet of Things). The multiple cameras on your Tesla, the sensors on security cameras, the chips inside medical equipment, fitness devices, machines on factory floors, kitchen appliances, smart speakers and many more will all connect to the internet and as these devices and the data they produce grows (and this growth will explode in the coming years), companies that provide the computing power and storage should benefit. Google has 146 distributed points of presence (POPs) in addition to their more traditional centralized data centers. There are a couple emerging companies that are really well counter-positioned for the next wave of the cloud, but Google should be able to take a nice cut of this growing pie.

(Note: for a great deep dive into the 3 major cloud providers, their products, and their comparative advantages along with their main competition, please read this tour de force; I highly recommend subscribing to my friend Muji’s service for a masterclass on all the major players in enterprise software, their products, and their business models).

Google is the poster child for defying base rates. It’s a $240 billion business that just grew revenues 41% last quarter and has averaged 23% sales growth over the past 5 years. Its stock price has compounded at 30% annually during that period, which is yet another testament to the idea that you don’t need an information edge nor unique under-followed ideas to find great investments in the stock market. I’ll have more to say about this topic and some implications for today’s market in the next post.

Conclusion

After this post-mortem, I still think my decision to sell the stock was a mistake. I think the change in capital allocation was hard to predict but I could have better assessed the likelihood there. I still think that the ad load on YouTube is potentially a problem, and I don’t like when companies begin extracting value at the expense of user experience. I worry about more of a “Day 2” mentality at Google. But Rishi’s heuristic has made me reconsider this issue. Perhaps this is something that can be lived with, just as I live with issues at every other company I own.

This was a general post about improving decision-making. Annie Duke points out how we crave certainty, but investing is about managing emotions, making decisions, dealing with uncertainty and risk, and being okay knowing that there will be both mistakes (bad decisions) and bad outcomes (being unlucky).

It’s what makes this game (and life itself) so interesting and fun.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at [email protected].