“The way to win is to work, work, work, work and hope to have a few insights.” – Charlie Munger

I came across a post on one of my favorite sites (Farnam Street) about Buffett on some fundamental keys to successful investing. I’ve always thought the most important aspect of investing is waiting for the proverbial “fat pitch”. As readers know, I’m a baseball fan (I love the game, and I love the numbers that are part of the fabric of the game).

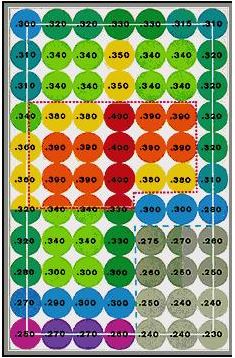

Ted Williams was famous for “waiting for the fat pitch”. He would only look to swing at pitches in the part of the strike zone where he knew he had a higher probability of getting a hit. There were parts of his strike zone where he batted .230 and there were other parts of the strike zone where he batted .400. He knew that if he waited for a pitch over the heart of the plate and didn’t swing at pitches in the .230 part of the strike zone—even though they were strikes—he would improve his odds of getting a hit and increase his overall batting average.

Similarly, Buffett waits for the .400 pitches. And as he’s pointed out, the beautiful thing about the stock market is there are no called strikes. You can never get behind in the count while passing on the .230 pitches and waiting for the .400 pitches.

The concept of “waiting for the fat pitch” is one that is often talked about in investing. Despite the well-known baseball metaphor, it’s still one of the most valuable concepts in investing. “There are no called strikes on Wall Street” is something that is often stated, but rarely practiced. Investment managers are paranoid about falling behind in the count. Part of this behavior is what leads to the various inefficiencies that occur in the market.

Here’s a clip that Farnam Street referenced from a 2011 interview with Buffett talking about this topic:

Warren: If you look at the typical stock on the New York Stock Exchange, its high will be, perhaps, for the last 12 months will be 150 percent of its low so they’re bobbing all over the place. All you have to do is sit there and wait until something is really attractive that you understand.

And you can forget about everything else. That is a wonderful game to play in. There’s almost nothing where the game is stacked in your favor like the stock market.

What happens is people start listening to everybody talk on television or whatever it may be or read the paper, and they take what is a fundamental advantage and turn it into a disadvantage. There’s no easier game than stocks. You have to be sure you don’t play it too often.

This concept is obvious to many value investors, but I always find it useful to keep in mind. The philosophy was also brilliantly articulated by Charlie Munger in a well-known talk he gave in 1994, called The Art of Stock Picking.

Munger describes the stock market as a pari-mutuel system—a system that is largely efficient, but not completely efficient. It can be beat, but the key is waiting for the “mispriced bet”. And the first step is investing in businesses that you can understand.

Pick Your Spots

Munger illustrates the circle of competence concept by describing the edge that can be carved out by a hard working individual who desires to become the best plumbing contractor in Bemidji (a small town in Minnesota of around 13,000 people):

“Again, that is a very, very powerful idea. Every person is going to have a circle of competence. And it’s going to be very hard to advance that circle. If I had to make my living as a musician, I can’t even think of a level low enough to describe where I would be sorted out to if music were the measuring standard of civilization.

“So you have to figure out what your own aptitudes are. If you play games where other people have the aptitudes and you don’t, you’re going to lose. And that’s as close to certain as any prediction that you can make. You have to figure out where you’ve got an edge. And you’ve got to play within your own circle of competence.

“If you want to be the best tennis player in the world, you may start out trying and soon find that it’s hopeless—that other people blow right by you. However, if you want to become the best plumbing contractor in Bemidji, that is probably doable by two-thirds of you. It takes a will. It takes intelligence. But after a while, you’d gradually know all about the plumbing business in Bemidji and master the art. That is an attainable objective, given enough discipline. And people who could never win a chess tournament or stand in center court in a respectable tennis tournament can rise quite high in life by slowly developing a circle of competence—which results partly from what they were born with and partly from what they slowly develop through work.

“So some edges can be acquired. And the game of life to some extent for most of us is trying to be something like a good plumbing contractor in Bemidji. Very few of us are chosen to win the world’s chess tournaments.”

The good news is that the stock market is filled with opportunities (10,000 opportunities in the US alone), and most people—if they have the will and the work ethic—can carve out an advantage in some small corner of the market not unlike the one that the best plumbing contractor in that small Minnesota town has.

Opportunities Abound (As Evidenced By 52 Week High/Low Gaps)

I got to thinking about Buffett’s comment about 52 week high prices being 50% higher than 52 week low prices.

This argument against market efficiency has always been one of the most compelling ones to me. There is just no logical way to explain why large, mature businesses can fluctuate in value by 50% on average in any given year. It makes no sense that the intrinsic values of large mature businesses can change by tens of billions of dollars in a matter of months—and this dramatic price fluctuation occurs on a regular basis—in fact, every year.

For instance, let’s just start by taking American business at large, using the S&P 500 as a proxy:

- The S&P 500 index is 21% higher than its level just one year ago. This begs the question: Are the 500 largest American businesses really 21% more valuable (or nearly $4 trillion more valuable collectively) than they were just 1 year ago? Unlikely…

- To look at it from another timeframe: the S&P index 3 years ago today (9/8) closed at 1186. It is now 69% higher 3 years later. Are American businesses really worth 169% of what they were just 36 months ago?

These might be obvious statements to fellow value investors, but I’m always interested in displaying these numbers on 52 week highs and lows, as I think it’s the most compelling argument against the efficient market hypothesis.

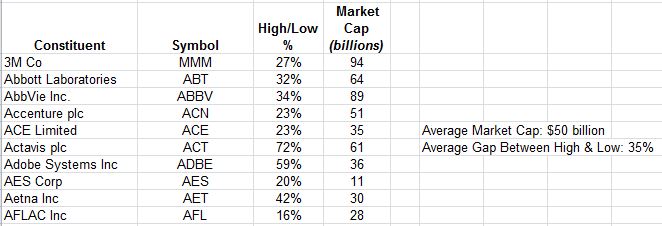

Here is a list of the 52 week highs and lows of 10 stocks selected from the S&P 500. I simply looked up a alphabetical list of the S&P 500 constituents and picked the first 10 stocks on the list.

S&P 500 Random Sample of 10 stocks (first 10 in alphabet):

So even for 10 of the largest companies in the US, the average high was 135% of the average low, not far from Buffett’s 150% statement, which applied to a much larger universe with more opportunities (the NYSE). It’s remarkable to me that a sample list of stocks with an average market cap of $50 billion can have market valuations that fluctuate by as much as 35% on average—or to put it in dollar terms, around a $17 billion yearly fluctuation.

And this is in a year where the volatility has been well below normal (the VIX is currently at 12). These 12 month ranges would be much wider in a year like 2011.

Since $50 billion market capitalizations represent some of the largest, most mature companies, let’s take a look at a list of smaller companies, whose values are often assumed to fluctuate much more. And remember, greater volatility brings greater opportunity for investors as the more a stock fluctuates around its true value, the larger the potential gaps are between price and intrinsic value.

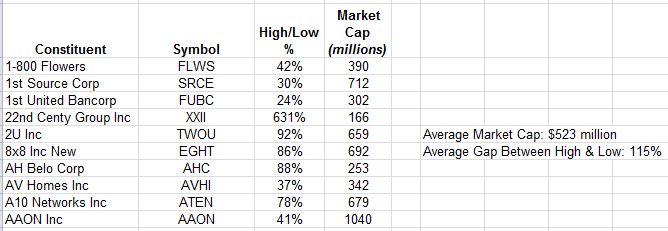

Here is a random sample of ten Russell 2000 stocks (again, this is the first 10 in the alphabet):

As expected, this list has a much greater range between the average 52 week high and 52 week low. The average high is 215% of the average low for these 10 stocks (in other words, the average high was 115% higher than the average low)!

Some might notice the outlier of 631%. Taking this outlier out of the list, we still have a 58% gap between the average high and low of the other 9 stocks.

Obviously this list tells us nothing about the intrinsic value of these stocks—only that the prices fluctuate widely. But it should be fairly obvious that prices are fluctuating much more than intrinsic values—which provides us with opportunity.

Clearly, there are a lot of opportunities in the pari-mutuel system known as the stock market. The key is to remember the plumbing contractor in Bemidji that slowly carved out his niche and gained an edge over all the other plumbers in that town. Keep carving out your niche. Spend hours and hours reading about things that interest you. Work hard. And patiently wait for opportunities that are easily identifiable and obviously mispriced.

You may not find yourself in a chess match against Bobby Fischer, but you might be able to conquer the plumbing business in a small town in northwestern Minnesota.