“You don’t have to know a man’s exact weight to know that he’s fat.” – Ben Graham

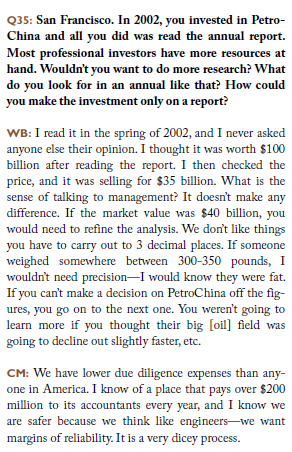

I was reading through some notes from the 2008 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting and one of the questions grabbed my attention. The question was pertaining to Warren Buffett’s decision to purchase stock in PetroChina back in 2002. Basically, the questioner was surprised that Buffett made such a sizable investment after a seemingly small amount of due diligence saying “all you did was read the annual report… Wouldn’t you want to do more research?”

Here is the question along with Buffett’s response:

I think think this displays one of the keys to Buffett’s success in the public equity markets that he has used throughout his career… namely, waiting to notice a huge gap between the value of a business and the price that you can buy the stock for.

Also, I think it’s interesting to note how he simply read the report, came up with a value, and only then checked the price. This is something that removes a lot of bias that comes when you know the price of the stock before trying to value it. Most investors will subconsciously anchor everything toward the current stock price. It would be hard to value PetroChina at $100 billion if you knew going in that the market was valuing it at $35 billion.

(Note: this is one of the reasons I enjoy valuing every spinoff situation. Normally, you don’t know the market valuation until the spinoff begins to trade, which allows you to come up with an intrinsic value ahead of time without any reference to the stock price. It can be a useful exercise.)

This appears to be what Buffett did with PetroChina. He loves reading reports, and you get the impression that he picked up the report one day in the spring of 2002, read through it, came up with a rough value of the business, then noticed that he could buy the stock for roughly a third of his estimated value of the business.

Of course, he was able to make this simple, seemingly quick decision to buy PetroChina stock because of his enormous foundation that came from the countless hours of reading and accumulating a bank of knowledge. This informational bank allows him to quickly compute the probabilities of various outcomes for each investment. But the takeaway is that the decision should be based on a few simple variables, and it should be a relatively easy decision. It’s easy to know that a $100 billion company that is currently priced at $35 billion is a bargain.

Indeed, a bargain it was back in 2002:

Buffett purchased a stake in PTR between 2002 and 2003 at a cost of $488 million. He sold this stake in 2007 for $4 billion, netting Berkshire a gain of 8 times its initial investment. The capital Buffett put to work in PetroChina compounded at about 55% annually between 2002 and 2007.

The quote that I referenced at the top of this post from Graham is one that I always enjoy keeping in mind when valuing businesses. The idea is not to obsess over the details, but to understand the big picture.

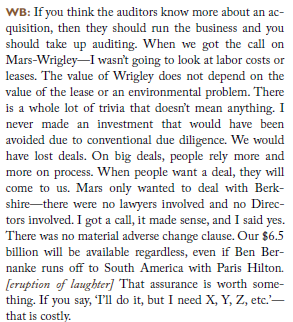

Buffett finished his answer to the question with another example:

It’s interesting to hear him say “I never made an investment that would have been avoided due to conventional due diligence.”

To Sum It Up

I recall Joel Greenblatt saying something similar when asked about diving deep into footnotes in annual reports. He basically said that he reads the footnotes also, but he likes to keep the big picture in mind. Things like how good is the business (what returns on capital does it generate?) and how cheap is it (what is the earnings yield?).

Each investor has different ways of analyzing and evaluating investment opportunities, but I definitely think that keeping things simple, and keeping the big picture in mind is crucial to maintaining a margin of safety and establishing superior results over time.

Perhaps the best way to sum up this post is to quote the 18th century German poet Christoph Martin Wieland who once said:

“Too much light often blinds gentlemen of this sort. They cannot see the forest for the trees.”

I’m not sure if Wieland was referring to investment managers, but his words are certainly applicable to our chosen trade.

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, dressme.co.nz/ball-dresses.html”>LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

To read more of John’s writings or to get on Saber Capital’s email distribution list, please visit the Letters and Commentary page on Saber’s website. John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.