“One of my friends—a noted West Coast philosopher—maintains that a majority of life’s errors are caused by forgetting what one is really trying to do.” – Warren Buffett, 1965 BPL Partnership Letter

I’ve read a few things lately discussing the benefits of designing a “tax-efficient” investment strategy. I’ve said this before, but I think there is a significant misunderstanding on the tax benefits of a low-turnover portfolio, and there is an even larger misunderstanding on the concept of turnover itself.

I’ve commented on portfolio turnover previously—turnover is neither good nor bad. It gets a bad connotation—especially among value investors—because many people think higher turnover (and more investment decisions) leads to hyperactivity and trading—and eventually results in investment mistakes. While this may be true in many cases, investment mistakes are not due to turnover—they’re due to making investment mistakes, plain and simple. I do believe that too many decisions may lead to this result—and I’m a fan of concentration and a relatively small number of stocks in my portfolio. But it is really important to understand—turnover in and of itself is neither good nor bad.

In fact, as I’ve said in a previous post, turnover is one of the key factors of overall portfolio performance. Just like a business (assuming a given level of tax rates, interest rates, and leverage) achieves its return on equity by two main factors—asset turnover and profit margins—so too does the return on equity (or CAGR) of an investment portfolio get determined by these two factors.

But this post is not about turnover, it’s about taxes. I bring this up because often I find investors lamenting the issue of taxes—especially when it comes to capital gains on their investment portfolio.

I have some thoughts on this topic of taxes and turnover, which I’ll share in the next post. I was going to reference a short passage of the 1965 Buffett partnership letter where he addresses this very same issue. But I thought I’d just post a slightly condensed version of the whole passage here, because I think it’s a good concept to think about.

Here are a few passages that I pieced together from the 1965 Buffett commentary on taxes (emphasis mine):

“We have had a chorus of groans this year regarding partners’ tax liabilities. Of course, we also might have had a few if the tax sheet had gone out blank.

“More investment sins are probably committed by otherwise quite intelligent people because of “tax considerations” than from any other cause. “One of my friends—a noted West Coast philosopher—maintains that a majority of life’s errors are caused by forgetting what one is really trying to do.”…

“Let’s get back to the West Coast. What is one really trying to do in the investment world? Not pay the least taxes, although that may be a factor to be considered in achieving the end. Means and end should not be confused, however, and the end is to come away with the largest after-tax rate of compound. Quite obviously if the two courses of action promise equal rates of pre-tax compound and one involves incurring taxes and the other doesn’t, the latter course is superior. However, we find this is rarely the case.

“It is extremely improbable that 20 stocks selected from say, 3000 choices are going to prove to be the optimum portfolio both now and a year from now at the entirely different prices (both for the selections and the alternatives prevailing at a later date. If our objective is to produce the maximum after-tax compound rate, we simply have to own the most attractive securities obtainable at current prices. And, with 3,000 rather rapidly shifting variables, this must mean change (hopefully “tax-generating” change).

“It is obvious that the performance of a stock last year or last month is no reason, per se, to either own it or to not own it now. It is obvious that an inability to “get even” in a security that has declined is of no importance. It is obvious that the inner warm glow that results from having held a winner last year is of no importance in making a decision as to whether it belongs in an optimum portfolio this year.

“If gains are involved, changing portfolios involves paying taxes…

“I have a large percentage of pragmatists in the audience so I had better get off that idealistic kick. There are only three ways to avoid ultimately paying the tax: 1) die with the asset—and that’s a little too ultimate for me—even the zealots would have to view this “cure” with mixed emotions; 2) give the asset away—you certainly don’t pay any taxes this way, but of course you don’t pay for any groceries, rent, etc.. either; and 3) lose back the gain—if your mouth waters at this tax-saver, I have to admire you—you certainly have the courage of your convictions.

“So it is going to continue to be the policy of BPL to try to maximize investment gains, not minimize taxes. We will do our level best to create the maximum revenue for the Treasury—at the lowest rates the rules will allow.”

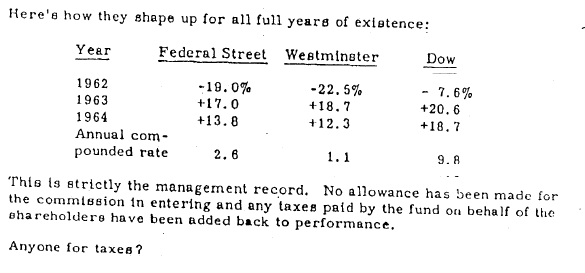

Buffett ends the section with a tongue-in-cheek reference to the “tax-efficient” funds of his day:

I thought these were interesting comments—especially regarding Buffett discussing “changing portfolios”, i.e. portfolio turnover. A portfolio of stocks one year will almost certainly not be the same optimum portfolio with the same risk/reward the next year. This implies that the portfolio should be more dynamic—always hunting for value.

Buffett doesn’t operate this way now, but it’s by necessity not by choice. There is only so much you can do when your stock portfolio is over $100 billion. But in the partnership days, there was higher turnover, higher taxes, and higher returns.

Related Posts: