I often get asked the question, “what is your edge”? The question comes up so often, and I feel like there is such a misunderstanding around what edge is and where it exists today that I continually feel compelled to write about it in these letters. Institutional investors seem especially interested in this question, and the edge that they are almost always looking for is some form of informational edge or insight that the rest of the market isn’t aware of. The problem is that this edge doesn’t exist anymore. Everyone understands that there is no info edge in Facebook or Apple. But there isn’t any info edge in smaller stocks either, at least not in a meaningful way that can be reliably utilized.

I’ve observed over the years that whatever information an investor believes to be unique is almost always understood by many other market participants, and thus is not valuable. The mispricing is not in the stock itself, but in the investor’s own perception of the value of information: it’s worth far less than they believe it is. Information is now a commodity, and like the unit price of computing power that provides it, the value has steadily fallen as the supply and access to it has skyrocketed.

Black Edge

I read a great book called Black Edge, which describes the trading strategy of Steve Cohen and SAC Capital. The traders at SAC categorized edge in three ways:

- White Edge: this was public information that wasn’t worth much to them because anyone could find it

- Gray Edge: this was valuable non-public information where it was uncertain if it was okay or illegal to use

- Black Edge: Clearly illegal inside information

The traders would hunt for gray edge all the time, and some engaged in black edge. The firm spent hundreds of millions of dollars they collectively spent on research was all designed to figure out if a stock was going to go up or down a few dollars in a short period of time, usually after an earnings announcement or some other significant event. These traders were moving billions of dollars around with no concern for what the company’s long-term prospects were, other than how those prospects might be viewed by other traders in the upcoming days.

Everything was purely focused on how the stock price would act in the very short term. It’s how the firm operated, and it’s how portfolio managers and analysts earned their bonuses. Everything depended on the short-term, and as a result, investment decisions were made that had nothing to do with long-term value and everything to do with short-term stock price.

This worked for SAC. Even before they committed a crime, they were very successful at betting on short-term moves. But reading about their strategy is refreshing because it solidifies two things that I already am very convinced of:

First, I have no informational edge, I don’t think anyone else has one either. But I don’t think you need one. This is fortunate, because it’s a game that is very hard to win. Reading about SAC’s resources reinforces that belief. It’s similar to how Ray Dalio advises people to diversify and invest in various asset classes and hold for the long-term, because “we are spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year to try and figure this game out, we’ve been doing this for 40 years, and we still don’t know if we’re going to win.” I’m not interested in trying to compete in a game that is that difficult to win.

Second, the investor who is willing to look out three or four years will have a lasting edge because the more money that gets allocated for reasons other than a security’s long-term value, the more likely it is that the security’s price becomes disconnected from that long-term value. In short, the deterioration of the info edge has actually increased the size of the “time horizon” edge.

This is a different kind of edge. The traders at SAC weren’t even discussing this type of edge. It wasn’t even on their radar, because they had no interest in the long game. But this is the reason that the time horizon edge exists, and I think has only gotten stronger as markets have become faster and the information has become more easily available. In fact, the liquidity that is provided by short-term traders adds to the volatility of stock prices, which creates more opportunities for long-term investors.

Price of Time Horizon Edge

Note that the time horizon edge isn’t a magic bullet. There is a reason why investors don’t want to own certain stocks at certain times. No one wanted to own Bank of America in 2016 because they were worried about recessionary risks and low oil prices and what might happen to the stock if those risks materialized. It was priced at around 7 times normal earning power, but investors thought (probably accurately) that it would fall more if the economy slipped. No one wants to own a stock that they think will go down in the next 6 months, even if they think in three years it will be worth much more.

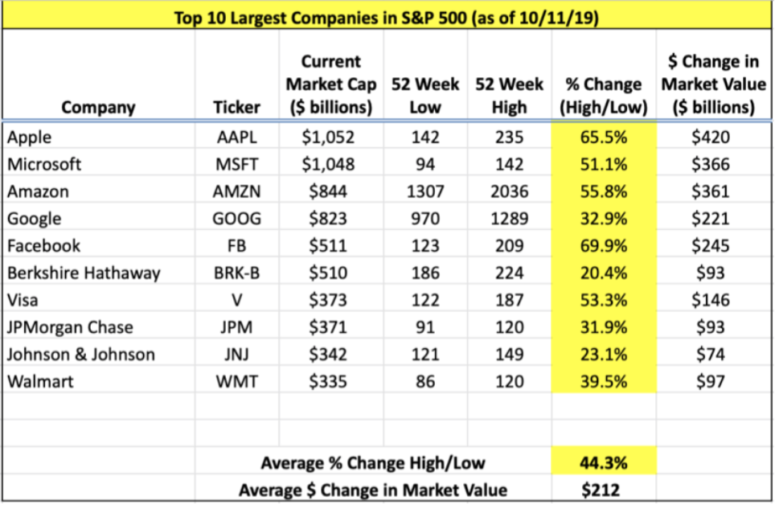

The time horizon edge could be summed up this way: the price of gaining this edge is the volatility that could occur in the near term. You have to be willing to accept the possibility that your stock will go down before it goes up. Very few investors are willing to pay that price, which is why even large cap stocks can become disconnected from their long term fair values:

Stock prices move much more than true values do even in the largest stocks, which by definition causes mispricing at times. This isn’t due to a lack of information, it’s simply good old-fashioned human nature, and unlike the price of semiconductors or the value of information, human behavior is not going to change. The biggest edge is in understanding this simple concept, and then being prepared to capitalize on it when it’s appropriate.

This is Saber’s game plan, and I will do my best to implement it.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at [email protected].