Last week, I came across this video of Stewart Horejsi, one of a small, but growing list of billionaires who have made their fortune solely because of their investment in Berkshire Hathaway.

This was a really interesting story about a guy who began buying Berkshire stock in the 1980’s at around $300 per share. There are many other stories of people who became rich by investing with Buffett. Compounding at well over 20% per year for decades will do that for you. But the stories never get old (at least for me). It’s always interesting to hear from someone who comes off as being just a regular individual investor who made two incredible choices:

- Invest in Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway

- Do nothing for decades, holding BRK and letting Buffett do the work compounding you initial investment over 500 fold (i.e. $100,000 initial investment in the early 80’s turned into $50 million)

The first choice might have been fortuitous. The second was certainly the most intelligent, and probably the most difficult.

One thing I thought of after watching this short video… Unlike some of Buffett’s early partners from the 50’s and 60’s, Horejsi didn’t discover Buffett until around 1980. By then, Berkshire Hathaway stock had grown exponentially from $7 per share all the way to around $265, where Horejsi started buying it. In fact, shortly after his purchase, it went from $265 to $330 in just a few weeks, and Horejsi was buying a few shares all along the way.

Here are Horejsi’s initial purchases of Berkshire Hathaway:

- His first purchase was 40 shares at $265

- Two weeks later he bought 60 shares at $295

- Four weeks later he bought 200 shares at $330

Incredible to think that these were the initial purchase decisions that would be the foundation for his billion dollar fortune. Soon after his initial purchase the stock reached $1000. Horejsi kept buying. Imagine what a chart of BRK looked like in the early 80’s, having gone from a low of $7 to current price of over $1000. But it was still an incredibly cheap stock relative to its intrinsic value.

So Horejsi kept buying even after it immediately rose. And over the years, he kept buying despite the stock rising many multiples from his original purchase price.

The combined decisions to buy, keep buying, and not sell allowed him to compound his capital into an unthinkable amount.

The Power of Compounding

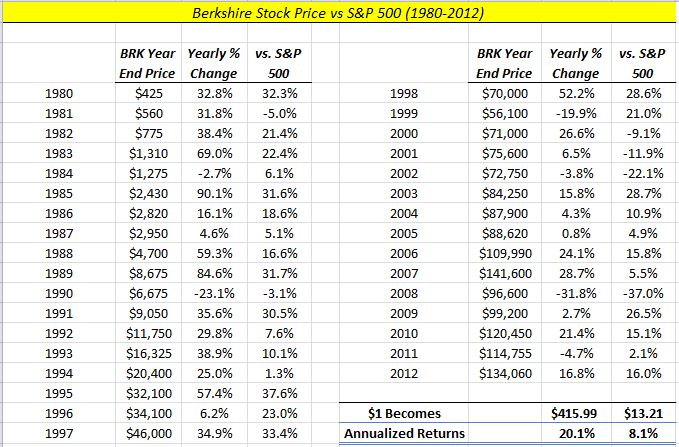

Take a look at Horesji’s long term results via holding BRK.A shares over time:

Wow….

Mohnish Pabrai once talked about a guy who set up a mutual fund that simply bought and held Berkshire A shares. Looking at these results, which trounce the vast majority of mutual funds and hedge funds, you can understand that logic!

More seriously, this example demonstrates the power of finding what I call a true compounder. A basic definition of a compounding machine is a company that can produce high returns on capital and can redeploy that capital continuously at similar high rates of return.

A company that is a net consumer of cash is usually value dilutive over time. A company that is a net producer of cash is value accretive over time. The cash allows them to return capital via dividends or buy back shares. But a company that can both produce cash and reinvest it in the business at ever persistent high rates of return is a long term investor’s dream, because it allows compounding to work its magic.

Buffett figured this out very early in his career.

Compounders Are Rare Birds

Most of my own investments are in businesses that I think are significantly undervalued, but ones that I would sell at a certain higher price. Thanks to Ben Graham’s Mr. Market, there are always opportunities to buy undervalued merchandise and sell it at a later time as it reaches fair value. This is an acceptable, methodical (and profitable) investment strategy. This type of investment is still passive, it’s still low turnover, it’s just not a “forever” type of holding. There are reasons to sell… The stock might reach fair value, or the business might deteriorate. Often, there are other attractive reinvestment opportunities that trump the future rate of return of current holdings that have appreciated.

But compounders are different… in the case of the Berkshires, the Teledynes, the Markels, the Fairfaxes, they are almost perpetually undervalued. The hard part is not necessarily identifying the compounder (although that’s not easy), but deciding if the business still continues to possess the ability to produce high internal rates of return. i.e. It certainly was a compounder, but is it going to compound going forward?

It’s hard because when a stock doubles, triples, or goes up 10x, there is a tendency to think that it has become too richly valued. Imagine how high Berkshire stock must have looked after going from $7 to $300. Or to $1000. Or to $5000. Or to $10,000, $20,000, $50,000, $100,000, $150,000, etc…

Compounders Reduce Reinvestment Risk

The other benefit of owning compounders is that they essentially eliminate reinvestment risk, i.e. the ever challenging issue of buying undervalued stocks, selling them as they reach fair value, and finding new undervalued assets to reinvest the profits. This is what Buffett has been doing for 50 years. It’s what we all have to do as investors. We allocate capital… ideally at high rates of return.

Some of this allocation is done directly (buying and selling stocks in our portfolio). Some of it is done indirectly (via owning a business, or businesses, where management makes the capital allocation decisions for us). So it’s a combination of direct and indirect capital deployment. The former involves us making decisions. The latter is completely passive, done by management of the stocks we own.

For the few patient investors like Stewart Horejsi, the complication of reinvestment risk was removed, and so was the work. Buffett did the heavy lifting for him — reinvesting and redeploying capital better than just about any other investment manager in history and making Stewart Horejsi a unheralded billionaire.

Here is the Bloomberg article and the interview with him below… Also, you may want to read (or re-read as I did) the Buffett chapter in John Train’s book–Horejsi mentioned that that chapter was the driving force behind his initial purchase of BRK.