“The boom is drawn out and accelerates gradually; the bust is sudden and often catastrophic.”

– George Soros, Alchemy of Finance

There was a very interesting article in the Wall Street Journal a few days ago on the story of “the swift rise and calamitous fall” of SunEdison (SUNE). Like a number of other promotional, Wall Street-fueled rise and falls, SunEdison became a victim of its own financial engineering, among other things. SUNE saw rapid growth thanks in large part through easy money provided by banks and shareholders. Low interest rates and deal hungry Wall Street investment banks helped encourage rapid expansion plans at companies like SunEdison, and provided the debt financing. Yield hungry retail investors, suffering from those same low interest rates on traditional (i.e. prudent) fixed income securities, helped provide the equity financing.

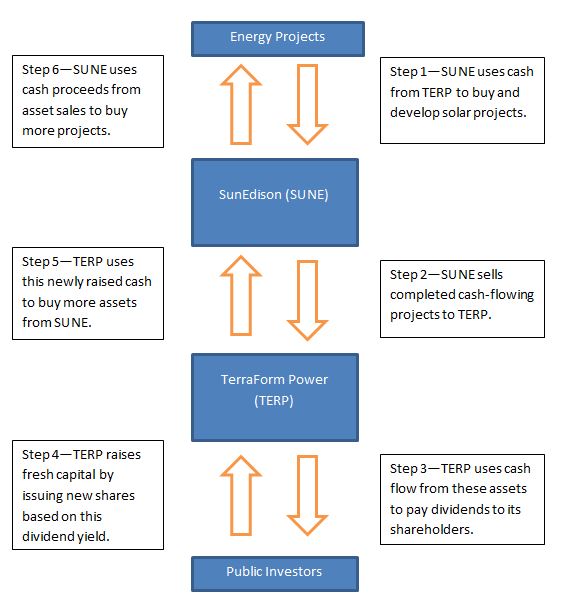

Just like MLP’s and a number of similar structures popping up in related industries, SunEdison provided itself with an unlimited source of growth funding by creating a separate business (actually a couple separate businesses) that are commonly referred to as yield companies, or “yieldco”. These yield companies are, in effect, nothing but revolving credit facilities for their “parent” business, and the credit line is always expanding (and the yield company is the one on the hook).

The scheme works as follows: a company (the “parent”) decides to grow rapidly. To finance its growth, it creates a separate company (the “yieldco”) that exists for the sole purpose of buying assets from the parent (usually at a hefty premium to the parent’s cost). To source the cash needed to buy the parent’s assets, the yieldco raises capital by selling stock to the public by promising a stable dividend yield. The yieldco uses the cash raised from the public to buy more assets from the parent, and the parent, in turn, uses these cash proceeds to buy more assets to sell (“drop down”) to the yieldco, and the cycle continues.

Thanks to a yield-deprived public, these yieldco entities often have an unlimited source of funds that it can tap whenever it wants (SUNE’s yieldco, TERP, had an IPO in 2014 that was more than 20 times oversubscribed). As long as the yieldco is paying a stable dividend, it can raise fresh capital. As long as it raises capital, it can buy assets from the parent, who gets improved asset turnover and faster revenue growth.

In Sun’s case, the yieldco is Terraform Power (TERP). (There is also TerraForm Global (GLBL) as well).

I made a very oversimplified chart to try and demonstrate the crux of this relationship:

It Tends to Work, Until it Doesn’t

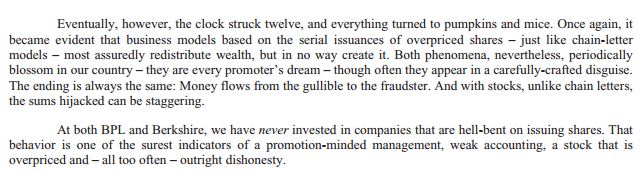

Buffett said this recently regarding the conglomerate boom of the 1960’s, whose business models also relied on a high stock price and heavy doses of stock issuances and debt:

If the assets that the yieldco is buying are good quality assets that do in fact produce distributable cash flow, (i.e. cash that actually can be paid out to shareholders without skimping on capital expenditures that are required to maintain the assets), then the chain letter can continue indefinitely. The problem I’ve noticed with many MLP’s is that the company’s definition of distributable cash flow (DCF) is much different than what the actual underlying economics of the business would suggest (i.e. a company can easily choose to not repair or properly maintain a natural gas pipeline. This gives them the ability to save cash now (and add to the DCF which supports the dividend) while not worrying about the inadequately maintained pipe that probably won’t break for another few quarters anyhow).

Another thing I’ve noticed with businesses that try to grow rapidly through acquisitions is that the financial engineering can work well when the asset base is small. When Valeant (VRX) was a $1 billion company, it had plenty of acquisition targets that might have created value for the company. When VRX became a $30 billion company, it is not only harder to move the needle, but every potential acquiree knows the acquirer’s gameplan by then. It’s hard to get a bargain at that point, but it’s also hard to abandon the lucrative and prestigious business of growth (note: lucrative depending on which stakeholder we’re talking about).

In Sun’s case, the Wall Street Journal piece sums it up:

“As SunEdison’s acquisition fever grew, standards slipped, former and current employees, advisers, and counterparties said. Deals were sometimes done with little planning or at prices observers deemed overly rich…. Some acquisitions proceeded over objections from the senior executives who would manage them, said current and former employees.”

So the game continues even when growth begins destroying value. Once growth begins to destroy value, the game has ended—although it can take time before the reality of the situation catches up to the market price.

Basically, it’s a financial engineering scheme that gives management the ability (and the incentives, especially when revenue growth or EBITDA influences their bonus) to push the envelope in terms of what would be considered acceptable accounting practices.

In some recent yieldco structures, I’ve observed that when operating cash flow from the assets isn’t enough to pay for the dividend, cash from debt or equity issuances can make up the difference—something akin to a Ponzi. Incoming cash from one shareholder is paid out to another shareholder as a dividend.

Even when fraud isn’t involved, this system can still collapse very quickly if the assets just aren’t providing enough cash flow to support the dividend.

Incentives

The incentives of this structure are out of whack. The parent company wants growth, and since it can “sell” assets to a captive buyer (the yieldco) at just about any price, it doesn’t have to worry too much about overpaying for these assets. It knows the captive buyer will be ready with cash in hand to buy these assets at a premium.

In Sun’s case, management’s incentive was certainly to get the stock price higher because, like many companies, a large amount of compensation was stock based. But their bonuses also depended on two main categories: profitability and megawatts completed.

Both categories incentivize growth at any cost—value per share is irrelevant in this compensation structure. You might say that profitability sounds nice, until you read how management decided to measure it:

“the sum of SunEdison EBITDA and foregone margin (a measure which tracks margin foregone due to the strategic decision to hold projects on the balance sheet vs. selling them).”

Hmmm… that is one creative definition of profitability. Not surprisingly, all the executives easily met the “profitability” threshold and bonuses were paid—this is despite a company that had a GAAP loss of $1.2 billion and had a $770 million cash flow loss from operations.

Growth at Any Cost

At the root of these structures is often a very ambitious (sometimes overzealous) management team. The Wall Street Journal mentioned that Ahmad Chatila, SUNE’s CEO, said that SunEdison “would one day manage 100 gigawatts worth of electricity, enough to power 20 million homes.” Just last summer, Chatila predicted SUNE would be worth $350 billion in 6 years, and one day would be worth as much as Apple. These aggressive goals are often accompanied by a very aggressive, growth-oriented business model, which can sometimes lead to very aggressive accounting practices.

I haven’t researched SunEdison or claim to know much about the business or the renewable energy industry. I’ve followed the story in the paper, mostly because of my interest in David Einhorn, an investor I admire and have great respect for. Einhorn had a big chunk of capital invested in SUNE.

David Einhorn is a great investor. He will (and maybe already has) made up for the loss he sustained with SUNE. This is not designed to be critical of an investor, but to learn from a situation that has obviously gone awry.

Parallels Between SUNE and VRX

The SUNE story is very different from VRX, but there are some similarities. For one, well-respected investors with great track records have invested in both. But from a very general viewpoint, one thing that ties the two stories together is their focus on growth at any cost. To finance this growth, both VRX and SUNE used huge amounts of debt to pay for assets. Essentially, neither company existed a decade ago, but today the two companies together have $40 billion of debt. Wall Street was happy to provide this debt, as the banks collected sizable fees on all of the deals that the debt helped finance for both firms.

Investing is a Negative Art

A friend of mine—I’ll call him my own “west coast philosopher” (even though he doesn’t live on the west coast)—once said that investing is a negative art. I interpret this as follows: choosing what not to invest in is as important as the stocks that you actually buy.

Limiting mistakes is crucial, as I’ve talked about many times. While mistakes are inevitable, it’s always productive to study your own mistakes as well as the mistakes of others to try and glean lessons that might help you become a little closer to mastering this negative art. One general lesson from the SUNE (and VRX) saga is that business models built on the foundation of aggressive growth can be very susceptible to problems. It always looks obvious in hindsight, but a strategy that hinges on using huge amounts of debt and new stock to pay for acquisitions is probably better left alone. Sometimes profits will be missed, but avoiding a SUNE or a VRX is usually worth it.

General takeaways:

- Be wary of overly aggressive growth plans, especially when a high stock price (and access to the capital markets) is a necessary condition for growth.

- Be skeptical of management teams that make outlandish promises of growth, and be mindful of their incentives.

- Be careful with debt.

- Try to avoid companies whose only positive cash flow consistently comes from the “financing” section of the cash flow statement (and makes up for the negative cash flow from both operating and investing activities).

- Simple investments (and simple businesses) are often better than complex ones with lots of financial engineering involved.

Here is the full article on SUNE, which is a great story to read.

——

John Huber is the portfolio manager of Saber Capital Management, LLC, an investment firm that manages separate accounts for clients. Saber employs a value investing strategy with a primary goal of patiently compounding capital for the long-term.

I established Saber as a personal investment vehicle that would allow me to manage outside investor capital alongside my own. I also write about investing at the blog Base Hit Investing.

I can be reached at [email protected].