“Google has a huge new moat. In fact, I’ve probably never seen such a wide moat.” – Charlie Munger, 2009

Google celebrated the 10 year anniversary of its IPO last week. Google is a company that I’ve never owned (unfortunately), but really admire. There are a few businesses I almost root for, like a fan of a football team. Costco, Fastenal, and Walmart among others are on the list. These are really high quality businesses that have made their shareholders wealthy over time.

Google is also on that list. I read an article in the Wall Street Journal that referenced Google’s initial prospectus (the filing that every company files with the SEC prior to listing its shares publicly). The prospectus is generally a great document to read, even for companies that have been around for a while. There are usually interesting nuggets of information, and many things you won’t find in the standard K and Q docs.

Anyhow, I read through the prospectus from 2004, and thought it would be interesting to take a look at a few numbers from Google’s first decade as a public company.

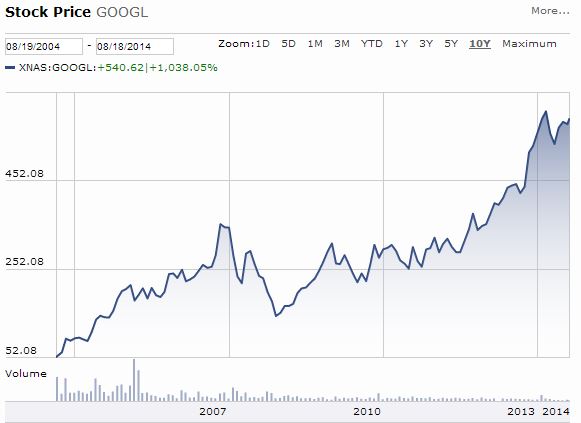

Let’s look at the results first. Take a look at the chart from the last 10 years:

The stock price appreciated from a split adjusted IPO price of $43 to $597 (that’s a 30.2% compound annual return for those shareholders smart enough to have held onto their stock through thick and thin over the past decade). And even more interesting, this 30% annual return came from a stock that sported a P/E ratio of around 60 when it began trading in 2004!

And this result has occurred even as Google’s multiple has shrunk by more than half (we hear about “multiple expansion” in investment theses all the time–this is “multiple contraction”. The P/E ratio was cut in half over 10 years even as the stock appreciated 11 fold).

I wrote a post last week about not caring about what the market does. If you own quality businesses that produce ever growing free cash flows and high returns on the capital they invest, then you shouldn’t worry about whether the S&P is expensive at 18 times earnings. And to be even more counterintuitive, sometimes stocks such as Fastenal, Walmart, and Google can turn out to be fabulous bargains even though they have seemingly expensive looking prices relative to earnings.

A Bargain Relative to Earning Power

As Ben Graham said in The Interpretation of Financial Statements:

“…the attractiveness or success of an investment will be found to depend on the earning power behind it. The term “Earning Power” should be used to mean the earnings that may reasonably be expected over a period of time in the future.”

After all, bargains are simply things priced for less than what they are worth. And the worth of a business—its intrinsic value—is measured against its future earning power, not the level of earnings it happened to achieve in the last twelve months. Google didn’t have a lot of the latter (when measured against its 2004 price), but it had plenty of the former.

In fact, you could have bought Google at a valuation of around $30 billion in 2004. To see what a bargain Google turned out to be (even with a high P/E), compare the $30 billion valuation in 2004 to the Google of 2014—one that made around $12 billion in after tax free cash flow last year and has $59 billion in net cash in the bank!

Indeed, Google was an undervalued stock in 2004.

A Look Back at the Decade of Google

However, my point of the post is not to lament the fact that most value investors missed out on Google. It may not have been prudent to invest in Google in 2004. It certainly wouldn’t have been for me. Very few investors had the foresight and the competence required to have taken advantage of a company such as Google in 2004—one that operated in a rapidly changing and newly developing search industry. But often times omitted investments (successful investments that made someone else rich) can be great learning exercises.

The point is to study a business that has been wildly successful, to try and uncover a few clues about why Charlie Munger thinks Google has one of the widest moats he’s ever seen.

This post is not this type of comprehensive study. But I thought it would be fun to take a look at some numbers from the past decade along with a few clips from the 2004 prospectus document.

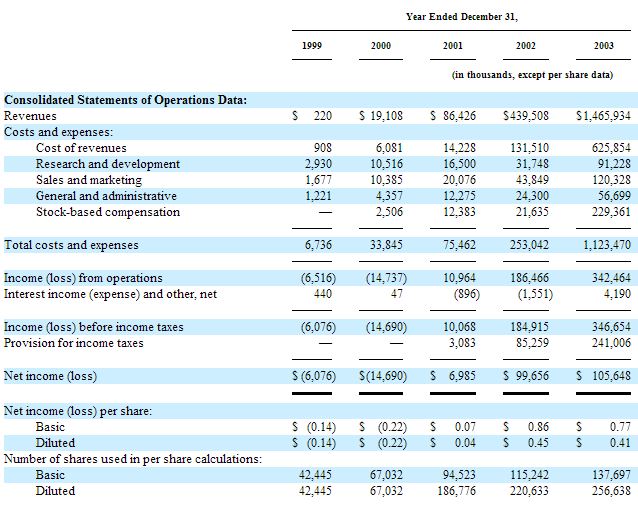

First, take a look at Google’s numbers from its birth in 1999 to the year before going public in 2004:

It’s incredible to think that Google was once a company that had $220,000 in revenue for a whole year. It’s now a company that grosses that much every 90 seconds.

Also notice that—unlike many tech companies—Google was very profitable at the time of its IPO with a 23% operating margin.

The Importance of Management and Time Horizon

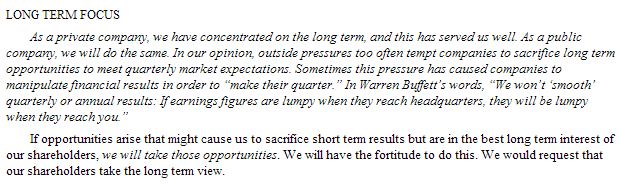

“We would request that our shareholders take the long term view.” –Google Original Letter to Shareholders, 2004

A deeper analysis would be needed to try to answer the questions about why Google has become so successful. But one thing to study is the management team and the founders.

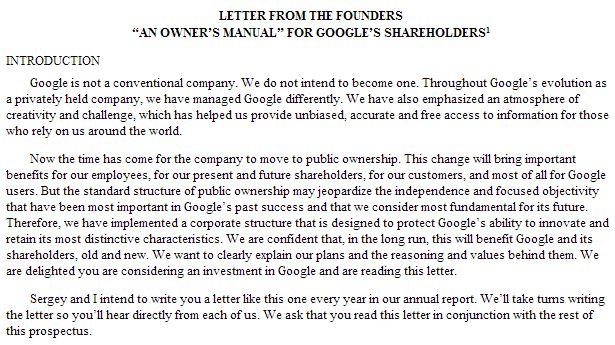

Like Jeff Bezos at Amazon, the founders write a letter to shareholders. Interestingly, Brin and Page also reference Warren Buffett’s essays, letters, and Berkshire’s “owner’s manual” as inspiration for their letters and communication with Google shareholders. Here is the original intro to the first letter that you can find on page 27 of the registration document from 2004:

Also like Bezos at Amazon, the founders at Google had very large aspirational goals, and they think for the long term:

Brin and Page knew from the beginning that a business should be focused on increasing earning power and shareholder value, not on meeting analysts’ expectations and quarterly numbers:

To Sum It Up

To summarize the post, here is a look at some of the numbers from Google’s 2004 results compared to the current numbers from 2014:

It’s hard to predict the next business that will compound at around 30% for a decade, but it helps to look for clues from the successful ones of the past. Great management teams are usually essential, and the qualitative factor of “thinking for the long term” should not be underappreciated.

I’ll leave the comprehensive analysis of Google for another time or for someone else, but I enjoyed paging through the old filing from 2004 and reading the letter to shareholders.

Have a great weekend!