This post is an expanded version of my comments on Wells Fargo from our recent mid-year letter to investors (please see here for the current letter; or to receive future updates from Saber Capital, please subscribe on the right of this page).

I have spent a lot of time over the years discussing the large US banks. I’ve invested in them on two different occasions over the past five years, and I think we are at a time where opportunity is knocking yet again. This time, I’m investing in Wells Fargo.

I did a podcast interview recently, and I discussed how my portfolio is strangely invested in large caps. I don’t anticipate this to be the case most of the time, and I don’t necessarily prefer this, but it’s where I’m finding value in the current market. As I’ve mentioned before, large cap stocks can often get significantly mispriced. I often use Apple as an example of this point, because despite being the most followed company in the world, it has compounded at roughly 30% annually in the past three years. Negative sentiment can at times cause large gaps to occur between stock prices and values, regardless of whether or not there is any “informational edge”.

Wells Fargo is not as good of a business as Apple, but I do think the stock is at a level that will meet my own investment hurdle rate going forward with a limited amount of risk.

Wells Fargo isn’t an exciting investment idea, and it’s not going to win any stock picking contests, but it is a very durable business with a very sticky customer base, and that leads to a very predictable revenue stream. That revenue stream produces a significant amount of free cash flow, almost all of which is being returned to shareholders via buybacks and dividends.

The stock currently trades at around 9 times earnings, meaning the combined yield is roughly 15% (we’re getting a 4% dividend and a 11% increase in our share of earnings from the buyback at this price). I think the yield is attractive, but I think the market is undervaluing the stock because of the negative headlines, and I think at some point this pessimism subsides, which will lead to a more reasonable valuation and an above average investment result from this level.

Culture and Incentives

I do think Wells Fargo had a major problem to address. I don’t think it was a cultural problem, I think it was an incentive problem. Employees were indirectly incentivized to act in a way that not only was bad for the customer, but also for Wells Fargo’s bottom line: most of the bad behavior involved opening accounts that produced no revenue, and thus cost the bank money as well as reputation damage.

Incentives drive behavior, good or bad. And without question, Wells Fargo’s behavior was bad prior to 2016. But two CEO’s have left the firm, and just as its safest to fly right after a crash, I think Wells has corrected the incentive issue, and is laser focused on ensuring that their customers are taken care of. I’ve noticed this as I do much of my business and my personal banking there. This case is also a testament to how sticky the big banks are.

I don’t think Wells Fargo has an issue that can’t be corrected in time, and I doubt their culture is much different than the other large banks like J.P. Morgan and Bank of America. All of the banks, just like most companies in other industries, attempt to sell their current customers additional products. I don’t think that business model is a problem. I think the way that Wells Fargo incentivized their employees to implement that business model was a problem. And as Charlie Munger likes to say, I think that was a cancer that can be removed from the patient, and I think in this case, the patient is going to make a full recovery.

Sticky Business

It’s painful to even consider switching banks. Updating the information for all of your monthly bills on a new autopay system is just one example of why inertia often wins in the business of consumer banking. Despite glaring headlines, lots of political rancor, and high-profile hearings, customers seem to have mostly yawned. Deposits stood at $1.3 trillion during the climax of the scandal, a level where they remain today. Deposits are the raw material that a bank uses to make its finished goods (interest income), and Wells Fargo has had no trouble maintaining its supply.

The company remains among the best banks in terms of funding costs and profitability. Returns on assets have remained strong, matching or even exceeding the ROA of its competitors.

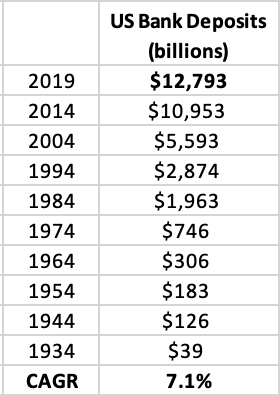

Deposit Growth

One reason Wells Fargo’s business is so durable is because overall deposit growth in the US banking system is so predictable. For 70 consecutive years, total deposits in the banking system have grown each and every year. There have only been 3 years since 1934 where deposits have declined, and all three years (1934, 1946, and 1948) were very small declines.

Regardless of economic conditions, deposits continue to grow, and deposits are the raw material that banks use to make money. Wells Fargo gathers these deposits cheaper than just about any other bank. The sticky nature of banking, the switching costs involved with changing banks, and Wells Fargo’s size makes it very likely they’ll continue to grab a piece of these new deposits as their current customers grow their wealth and save more money over time.

Fed Restriction

Another reason why I think the stock is cheap is because the Fed has restricted Wells Fargo’s ability to grow its assets. Basically, Wells can’t grow its balance sheet over $1.95 trillion until it proves to the Fed that it has addressed its management issues and board governance practices.

On the surface, this seems like a bad thing for Wells Fargo. A bank’s earning power is tethered to the size of its balance sheet; the assets are the raw material a bank uses to generate revenue, and without the ability to increase the amount of raw material, the only way earnings can grow is through efficiency gains (cost cutting).

However, I don’t think the growth restriction is all that bad. For one thing, when you have nearly $2 trillion in assets, you’re not going to be growing very much to begin with. Secondly, the Fed order is temporary, and will likely get released in the coming year or two. But regardless of when that occurs, I actually believe that a restriction on growth is not a bad thing for a large bank. Wells Fargo won’t be tempted to go after the marginal loans that many banks inevitably go after as the business cycle continues heating up and credit quality gets looser. The Fed’s restriction basically forces them to only take the most prudent loans, because there is no incentive to go after riskier loans in an effort to grow.

Buyback

Last week, the Federal Reserve published the results of their annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR). The CCAR and its cousin, the Dodd-Frank Act stress tests, are a big portion of the regulatory framework that the Fed uses to supervise the big banks in the United States. Part of this regulation gives the Federal Reserve the authority to the approve capital allocation program of the banks.

Basically, each bank submits the dollar amount of capital that they’d like to return to shareholders over the coming 4 quarters, and the Fed, based on their review of how the bank performed during the stress tests, either approves that amount or rejects it. In recent years, most of the big banks have built up sizable capital positions, and they’ve had no real trouble getting Fed-approval for their buyback and dividend.

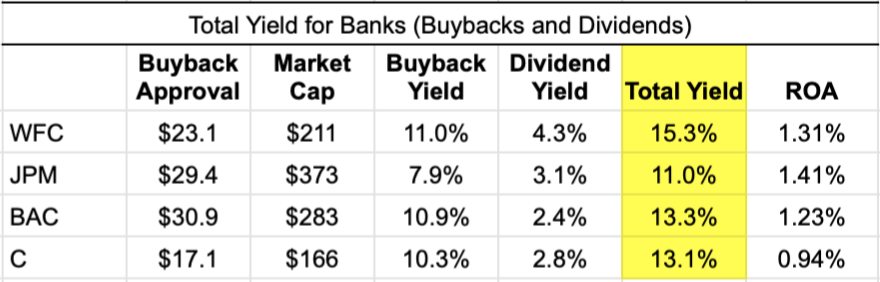

Here is a table showing the dollar amount (in billions) that the four largest banks are allowed to return to shareholders via buybacks. It then shows the “yield” for the buyback (which is the percentage of the total outstanding shares that the company could buy back in the next 12 months at the current price). It also shows the current dividend yield (each bank also got approval to raise their dividends). And finally, the total “yield” (buyback + dividend):

I think the amount of capital that each bank will return during the coming year is remarkable. Another thing I’d point out is that the buyback program at these banks is really predictable. If JPM gets approval to buy back $29 billion of stock, you can take it to the bank (no pun intended) that they will in fact use all of that authorization.

Programatic buybacks aren’t always a good thing (I’d prefer companies to have some method of estimating the intrinsic value of their stocks and then use that to determine the timing of their buybacks) but in this case, since the banks are undervalued, this predictable buyback works in shareholders favor in a big way. Also, as the stock price declines, each dollar is acquiring more value for remaining owners, which is why Buffett always points out that lower prices are better for long-term values.

For WFC, we’re getting a 4.3% dividend yield, and if the stock price doesn’t move, we’ll own a 11% greater piece of the company’s earning power in a year. The basic idea is that all of the cash earnings (and then some since the banks currently have more capital than they need) are coming back to us each year: partly as a dividend and partly as a bigger piece of ownership.

Over time, our investment result should roughly approximate this “yield”, and that’s even before any bump we might get from the market revaluing the shares (which I think could certainly occur with WFC trading around 9 times earnings).

Valuation

I estimate that Wells Fargo will earn roughly $100 billion of free cash flow over the next 4-5 years, which is about half of the current market cap. Because Wells Fargo has plenty of capital, it’s likely that all of those earnings will get returned to shareholders as dividends and buybacks.

After this year’s buyback, Wells will be left with around 4 billion shares outstanding. With no growth in overall earnings, this will equate to nearly $5.75 per share in earning power a year from now. At $46 per share, the stock trades at just 8 times that earning power. Another way to look at it: Wells Fargo is likely going to buy back around $40 billion worth of stock in the next couple years. Again, assuming the current level of overall earnings (no growth), we’ll have a business with over $6 of earning power and at 11 or 12 times earnings, a stock worth somewhere between $65 and $75. Including the hefty 4%+ annual dividend, that is 50-75% upside for a boring, staid bank.

Even at just 10 times earnings, we’d still reap a 15% annualized return over two years with no growth, thanks to the buyback and dividend.

I think there is upside potential as well: maybe the Fed releases their restriction, or maybe Wells gets its efficiency ratio more closely in line with competitors (the costs have risen as a result of the scandal, and some costs are likely to be permanent, but it’s likely some will subside as well).

But again, total earnings growth is not even necessary for this investment to work out quite well at this price.

To Sum It Up

We have a good business with a sticky customer base, a recurring free cash flow stream, and a predictable capital allocation program, but we have a stock that is undervalued because of significant pessimism. Wells Fargo is facing a similar negative sentiment that Facebook was (and still is) facing. I think the pessimism will subside eventually, and in the meantime, we’re getting a 15% total “yield” to wait for that appreciation to occur, which on its own is not a bad outcome.

It’s not an exciting company to invest in, but I think there is little chance of permanent downside at the current price, which makes it an attractive risk/reward investment.

John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

John can be reached at john@sabercapitalmgt.com.